GCC-Africa financial links are starting to evolve from aid to investment

Africa is not a prime target for Gulf banks, but when it comes to investment and development assistance, the financial relationship between GCC economies and sub-Saharan Africa is gaining momentum.

Impressive rates of economic growth, large populations and rich mineral resources hold clear attractions for portfolio investors seeking to diversify their global exposure.

By contrast, for newcomer banks, Africa is a tough challenge. Sub-Saharan countries have been a profitable niche market for banking groups with networks on the ground and the knowledge to engage safely in local lending, and trade and commodity finance. But without local connections and expertise, it is hard for outsiders to identify worthwhile banking business – apart from large resource projects – and manage it effectively.

However, foreign direct and portfolio investment are shaped by a different logic and sub-Saharan countries have begun to stir the interest of one or two influential GCC players.

Kingdom Holding

By far the most prominent is Kingdom Holding Company chairman Prince Alwaleed bin Talal bin Abdulaziz al-Saud. His group has established a private equity firm that specialises in Africa: Kingdom Africa Management Company.

Prince Alwaleed has cultivated high-level relations south of the Sahara, visiting Nigeria for talks with President Goodluck Jonathan in December 2011, and then travelling to Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi in August last year for further meetings with African leaders.

Kingdom Holding has been taking an interest in the continent for almost two decades, launching the South Africa Capital Growth Fund and the South Africa Private Equity Fund in 1995.

These were followed by the ZM Africa Investment Fund (ZMAIF) in 1997, targeting private equity investments in South Africa and other markets in the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) bloc. The fund focused on high-growth businesses, and as these have progressed it has been able to gradually divest from them. The next phase of the strategy was the creation of the Pan-African Investment Partners I (PAIP I) fund in 2003, with launch capital of $122.5m, followed five years later by Pan-African Investment Partners II. The latter finally closed in 2010 with $492m of capital.

The broader economic context for these funds has been the resilience of economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa, which was less affected by the global financial crisis and economic slowdown than most other regions of the world.

From 2004-08, sub-Saharan Africa’s real gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 6.5 per cent a year. Even in 2009, the year of the global crisis, it was 2.8 per cent, and it has since rebounded to the 5-6 per cent range. Smaller economies and those dependent on imported oil have generally performed well.

Social indicators are slowly improving in many countries and the continent is seeing the emergence of a substantial educated middle class, reinforcing political stability and enhancing demand for consumer goods and services.

The PAIP funds reflect the growing resilience of economic activity and demand within Africa itself. The first fund targeted profitable businesses in high-growth sectors all over the continent. The second has done likewise. Its major investments have included $20m in Buildworks, a power infrastructure and building materials firm based in South Africa, with presence in 13 other countries; e14.3m ($18.7m) in Thunnus Overseas, a tuna canning firm active in Ivory Coast, Madagascar and France; and e35m in Mixta Africa, a real estate developer with projects in Senegal, Mauritania and North Africa.

Gulf investors have been attracted to the resilience of economic growth in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa

Beyond investment, there is another key facet of the GCC states’ financial relationship with sub-Saharan Africa: their role as aid donors. This was pioneered by the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development (KFAED). As its name suggests, this was originally set up to assist other Arab countries, but from 1974, the list of potential aid recipients was extended to a wide range of other nations.

Financial assistance

The KFAED provides mainly concessional loans, technical assistance and training. Sub-Saharan countries are major recipients. Although the fund is particularly active in countries with large Muslim populations such as Senegal, Mali, Niger, Kenya and Tanzania, it also finances projects in many other African states.

The KFAED frequently operates as a co-financier, in partnership with other donors, to share the costs of major schemes.

By mid-April this year it had provided a total of KD482.6m ($1.7bn) in funding to West African countries, among which the biggest recipient (of KD95.4m) was Senegal, which has long cultivated close relations with Kuwait and other GCC states. Other major West African beneficiaries are Guinea (KD48.6m) and Ghana (KD39.6m).

Cumulative funding for central, Eastern and Southern Africa has amounted to KD358m, with the largest amounts going to Tanzania (KD50.9m) and Ethiopia (KD43.3m).

Sudan, administered within the Arab countries portfolio of the fund, has received KD227.4m; so far, separate data for South Sudan – independent since 2011 – is not available. Mauritania, also administered within the Arab portfolio, has received KD107.3m.

In sectoral terms, in Africa, the KFAED has given overwhelming priority to funding transport infrastructure, allocating KD205.2m to this in the centre, east and south of the continent, and KD271.8m in the west. Communications, energy, industry and agriculture are other favoured sectors, though not to the same extent.

Kuwaiti aid to sub-Saharan Africa tends to focus on the drivers for economic growth more strongly than on social sectors.

Supporting Africa

Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi are also substantial bilateral donors to Africa. The Saudi Fund for Development, established in 1975, has a long track record of sub-Saharan engagement. By 2009, Africa accounted for more than half the countries and more than half the projects the fund had financed.

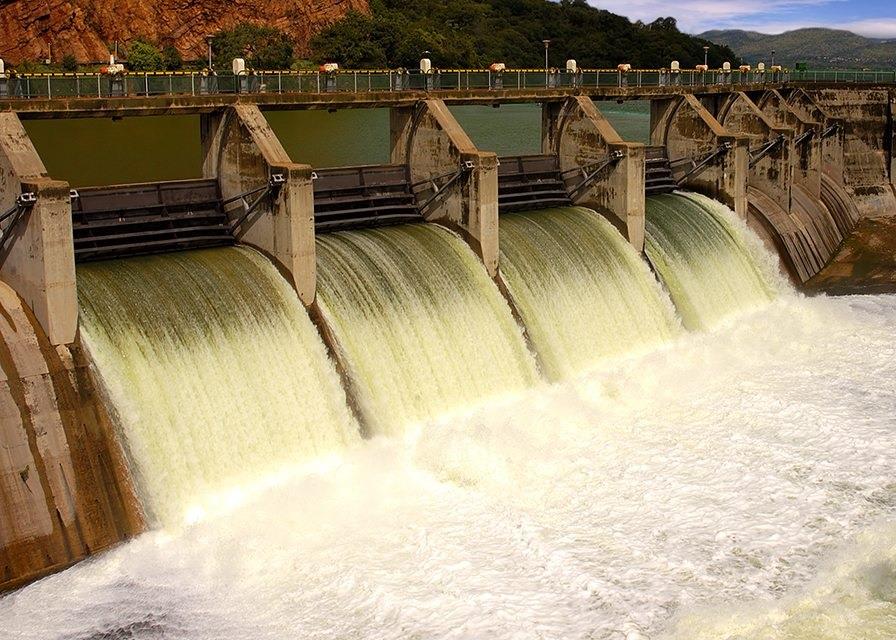

One of the most important projects it has assisted is the Marawi dam in Sudan, with a total support of $310m (including $100m channelled through the Saudi export programme). This accounted for more than 10 per cent of the cost of the massive project.

Other Gulf-based bilateral donors were heavily involved. The Kuwait Fund and Abu Dhabi Fund for Development contributed $200m each, Oman contributed $106m, and Qatar $15m.

The Saudi Fund has concentrated its aid to sub-Saharan Africa on a much narrower range of countries than the KFAED: Benin, Cape Verde, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Gambia, Mali, Mauritania, Sierra Leone and Uganda. The focus is often strategic infrastructure, such as an 86-kilometre section of road between Yamoussoukro and Snkarobo in Ivory Coast. In Mali, the fund has been part of the financing consortium for the important Taoussa dam on the Niger river.

In Benin, the Saudis have been supporting regional development through university institutions in provincial towns and being part of a regional hospital programme. In Uganda, they have been supporting the construction of 14 technical and vocational education institutes.

Overall, some SR15.6bn ($4.1bn) has been allocated to African projects by the Saudi Fund, which is about 47 per cent of all its activity. The figures cannot be directly compared with those from the Kuwaiti fund because they include North Africa; Arab states are not categorised separately.

The Abu Dhabi Fund for Development also has a history of significant engagement south of the Sahara, particularly in Sahelian countries and in East Africa. The fund has fewer than 100 staff.

Slow approval

As with any donor arrangements, the pace of development is to some extent dependent on the capacity of the recipient country to implement schemes. Only one project has been approved in Democratic Republic of Congo, one of Africa’s largest countries but one that is highly unstable and has serious governance problems. That was a package of balance-of-payments support back in 1987. By contrast, tiny Djibouti – stable and strategic – has benefitted from three funding allocations.

There is a flow of investment in Africa from the GCC, but it has been largely aid-based. As the continent matures and Gulf financial entities become more experienced, this is likely to change.

You might also like...

Ajban financial close expected by third quarter

23 April 2024

TotalEnergies awards Marsa LNG contracts

23 April 2024

Neom tenders Oxagon health centre contract

23 April 2024

Neom hydro project moves to prequalification

23 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.