JORDAN has an efficient, closely supervised banking sector and a well- run financial market, but is this all it needs for the new era of investment and economic change that now beckons? The general opinion, shared by officials and the private sector alike, is that Jordan has solid foundations but needs to do more to make itself attractive. There the consensus ends, and opinions differ about what needs to be done.

When it comes to banking, Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) governor Mohammed Nabulsi knows what he wants - bigger, stronger banks. 'Unless this is done,' says Nabulsi, 'banks won't be able to cope either with the expansion needed in the Jordanian economy nor in the West Bank, where the banking system is also expanding.'

The central bank has already asked local banks to raise their capital to JD 20 million by the end of 1996 and has introduced a range of incentives to encourage mergers among the 16 local commercial banks. Foreign banks have been requested to raise their capital to JD 10 million and Nabulsi has let it be known that the future extent of their operations could be constrained by the size of their capital.

Bankers have no strong objections to the capital increase although Nabulsi may be disappointed at how few are interested in mergers. A number of Jordan's banks, like many of its other businesses, are family enterprises which consider mergers as a last resort, preferring new share issues and the tapping of reserves as ways of meeting the capital requirement. Others feel that room should be left for small specialised institutions, especially in the investment field. 'A well managed small bank can also create its own niche and be master of an area,' says one investment banker.

Bankers are more unanimous in applauding the liberalisation measures which began with the floating of interest rates. The reforms have since moved on to permit lending in foreign exchange and to give banks far more freedom to invest their reserves abroad.

Many bankers part company with the governor over the CBJ's role in monitoring lending decisions. At present banks cannot lend more than 25 per cent of capital and reserves to a single customer or group of customers. Every facility over 10 per cent of a bank's capital and reserves has to be approved by the CBJ. And the central bank also groups all customers to whom a bank has loaned 7 per cent or more of capital and reserves and restricts total lending to four times capital plus reserves. 'The first restriction is common sense,' says one banker 'but the other decisions on lending should be left to the bankers themselves.'

Official and private priorities at the Amman Financial Market (AFM) can also diverge. AFM director-general Umayya Toukan presides over one of the best managed financial markets in the Arab world but he is far from resting on his laurels. He has drawn up a new law that includes the strengthening of regulations covering disclosure and insider trading and other measures to improve transparency. It requires brokers to increase their capital to JD 10 million within two years. There will be a single law governing the issue of financial paper, which will not be limited to the local currency, and there will be a securities and exchange commission.

Toukan is also keen to develop the AFM's regional and international profile. The AFM has now completed an agreement with the Bahrain market allowing for cross listing of stocks and negotiations for a similar agreement are under way with the Muscat Securities Market in Oman. The AFM is also exploring the possibility of listing Jordanian blue chips on the London Stock Exchange.

Not all of the AFM's brokers agree on the need to try so hard to attract foreign investment. Improve domestic conditions, they say, and foreign investment will take care of itself. Some of their concerns about the local investment climate have been addressed in new tax and investment legislation. The financial market law should cover most of their other concerns although many want the government to move further and faster to correct distortions in the economy.

The shareholders of a number of major public companies are also becoming impatient. A government role may have been essential to get major enterprises started 20 or 30 years ago but it is seen as out of place in a new free market environment. 'Having shares in the Jordan Petroleum Refinery Company is more like holding government bonds,' says one local investor, referring to a listed company in which the government sets the price of both raw materials and finished products and puts limits on profits and dividends.

Some observers see more profound challenges facing Jordan's financial system which derive from the character of the economy that has developed over the past 40 years. 'Jordan was a resource-poor country that lived on aid,' says one financial expert, 'and the banking system evolved around the guarantee of imports. We don't have experience in setting up and managing corporations and our officials have not grasped the idea of capital markets and still look on the AFM as a gambling centre.'

One reason why foreign investors are much talked about but little seen is because getting access to the market can be so problematic. The enthusiasm for the AFM shown by foreign fund managers over the past two to three years has been worn down by the mountain of regulations restricting market entry. The new investment law passed by parliament in late September treats local and foreign investors alike and lifts the requirement for foreigners to obtain permission from the prime minister before investing in the AFM. Whether conservative bureaucrats will come up with new hurdles to replace the old ones remains to be seen.

You might also like...

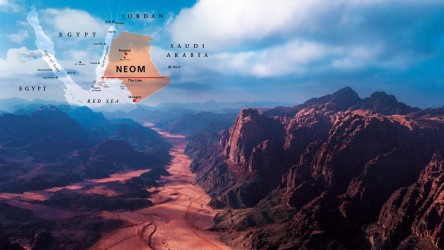

Neom seeks to raise funds in $1.3bn sukuk sale

19 April 2024

Saudi firm advances Neutral Zone real estate plans

19 April 2024

Algeria signs oil deal with Swedish company

19 April 2024

Masdar and Etihad plan pumped hydro project

19 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.