The departure of several prominent Brotherhood figures in September shows Qatar is keen for a united front in the face of Isis advance. But the diplomatic rift is far from healed

On 12 September, the Muslim Brotherhood-aligned, Egyptian-Qatari cleric Wajdi Ghanim posted a photograph online that showed him standing alone in a cavernous airport departure hall holding a large suitcase.

Above it was a quote from the Koran: He who migrates for Gods purpose will find a land of much opportunity.

The forlorn image was posted after Ghanim became one of several senior figures connected to the Brotherhood to have announced their departure from Qatar due to their host country coming under heightened political pressure from the other GCC states.

Major breakthrough

The departure of these Brotherhood figures, in an apparent capitulation by Doha, has been hailed by some analysts as a major breakthrough in healing the GCCs current diplomatic rift. But the exit of figures such as Ghanim alone will not resolve the complex issues at the heart of the blocs political problems.

The expulsion of this initial group of [Muslim Brotherhood figures] only scratches the surface

Theodore Karasik, Inegma

Qatar is doing this as a goodwill gesture, says Theodore Karasik, director of research and consultancy at the Dubai-based Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis (Inegma). Hopefully, there is more to come over the next few months. But at this time, the expulsion of this initial group of individuals only scratches the surface.

Qatars decades-long relationship with the Brotherhood has been an increasing source of disharmony in the GCC since the organisation saw a surge in influence in the wake of the 2011 Arab Uprisings, with affiliated parties winning elections in Tunisia and Egypt.

Tensions came to a head when Doha continued to support Egypts Brotherhood-backed president, Mohamed Mursi, while the other Gulf countries hailed his overthrow by the army last July.

States including Saudi Arabia and the UAE view the Brotherhoods democratic brand of political Islam as a threat to their own monarchies, with Riyadh even going so far as to label the organisation a terrorist group in March this year, saying it was one of several groups that are ruled from outside to serve political purposes.

Despite years of vocal criticism from the likes of the UAE and Saudi Arabia, until recently Doha has persisted in hosting exiled dissidents linked to the Brotherhood from Libya, Egypt and Syria, as well as sheltering members of other controversial groups including Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal, and maintaining close links with the Lebanon-based Shia militia movement Hezbollah.

The widening rift between Qatar and the rest of the GCC was exposed in dramatic fashion in March, when Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors from Doha, citing Qatars failure to abide by rules set out in the Riyadh Agreement. This refers to a deal brokered by Kuwait in November last year that aimed to diffuse tensions between Doha and Riyadh, and outlined terms for Qatars cooperation with the rest of the GCC in order to end its isolation, the full details of which were not made public.

The joint statement released by the three countries announcing the removal of the ambassadors said that Qatars emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, had failed to implement an agreement not to back anyone threatening the security and stability of the GCC, whether as groups or individuals via direct security work or through political influence, and not to support hostile media.

In the six months since the ambassadors left the country, external pressures have played a significant role in forcing Doha to compromise.

The most significant of these has been the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (Isis), the jihadist group that sent shockwaves through the Middle East in June, when it swept through Iraq seizing huge swathes of territory, including the countrys second-largest city, Mosul.

External pressures

Although there have been repeated accusations that Qatar has been funding Isis (something that would be unacceptable to its GCC peers), many analysts say there is little evidence to back these allegations and that the rise of Isis is more likely to be the source of the current drive for unity rather than a cause of dispute.

The further development of Isis represents a direct threat to all of the GCC states, says Christian Koch, director at the Geneva-based Gulf Research Center Foundation.

Even Qatar understands that support for the Muslim Brotherhood is one thing, but turning a blind eye to Isis and its policies is completely different.

While the advance of Isis has brought the GCC nations together in recent months, at the same time, certain actions by Doha have continued to infuriate Saudi Arabia and the UAE, deepening the blocs existing fractures.

Among the most problematic of these unresolved issues is Qatars continuing close ties to the Brotherhood. Comments by Qatari officials and the organisation about the departing Brothers have made it very clear that other forms of support from Doha for the Islamist organisation will continue.

Fundamentally, it is very difficult for Qatar to change its stance towards the Brotherhood, says David Roberts, a lecturer at Kings College London.

Firstly, its a historical policy, so unless hes going to unpick half a century of toleration towards the Brotherhood, its unlikely to change significantly. Secondly, its difficult for him to capitulate to regional pressure; this whole situation has become an issue of pride for Qataris, to not give in. Certainly, weve seen some movement to accommodate regional allies, but tacit support in the background at least is likely to remain.

Identity crisis

In his accession speech in June last year, Sheikh Tamim said that during his reign Qatar will remain the Mecca of the oppressed, repeating a phrase that was previously used by Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed al-Thani, who founded Qatar in 1971, and by his father and predecessor, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani.

This phrase has been interpreted by some analysts as a statement that sets Doha up as both an alternative and a challenger to Riyadhs political dominance, as well as putting its role as a supporter of embattled Muslim groups at the centre of the Qatari world view.

The Qataris have a vision for their homeland that is both ideological and cultural, and concerns the countrys position in the world, says Inegmas Karasik.

This vision is something [Sheikh Hamad], when he came to power, wanted to see Qatar develop in a certain way in order to have influence. It has become ingrained in Qatari society and it doesnt fit in with the rest of the GCC. That is where the problem lies.

Despite the atmosphere of cooperation that is currently being promoted by GCC leaders, Dohas ambition and views on political Islam are likely to continue to manifest themselves in ways that will put it at odds with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, including its stance on financing an array of militant groups across the Middle East and North Africa, through both official and unofficial channels.

Despite several high-profile overhauls of Qatari counter-terrorism legislation, the US has been highly critical of what it has dubbed Qatars permissive terrorist financing environment.

In a report published by the US Department of State in April, the Bureau of Counterterrorism stated that Qatari-based entities posed a significant terrorist financing risk, over the course of 2013 and that despite Dohas legal framework being robust, judicial enforcement and effective implementation of its counter-terrorist financing legislation was lacking.

This inefficient enforcement is no accident, according to Karasik, who says the state allows individuals to fund militant groups overseas as a way of increasing its influence without angering its neighbour states with overt interference.

Its an informal foreign policy that is likely to endure, he says. In Qatar, there are individuals and companies that function as foreign policy actors by giving money, recruiting or providing transport for militant groups in other countries.

Although Saudi Arabia and the UAE both criticise Qatar for meddling in other countries affairs, they are equally guilty of using their wealth to support political groups in the region, often picking groups that are at odds with those supported by Qatar.

During the early days of the Syrian civil war, Doha and Riyadh supported rival factions within the Free Syria Army, something some analysts cite as exacerbating fragmentation in forces fighting the regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

Proxy wars

There are allegations of financial support of a similar kind being directed towards groups in Yemen and the Palestinian territories, and the proxy war in Libya has seen a dramatic escalation in recent months.

According to US officials, the UAE secretly carried out bombing raids on Qatari-backed Islamist militias in Libya as recently as August, and on 14 September, Libyas Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thinni accused Qatar of sending three military planes loaded with weapons and ammunition to support the groups that had been bombed.

When Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the UAE withdrew their ambassadors from Doha in March, many Qatar-watchers speculated that other punitive measures could follow, with some fearing it could even be the beginning of the end of the GCCs three decade-old union in its current form.

The departure of Ghanim and his peers shows that despite the differences that exist within the GCC, both Qatar and its neighbours are willing to make at least a gesture towards compromise for the sake of unity.

If the events of the past few months do indeed mark the start of a new era for the GCC, it is likely to closely resemble the past era, with a slightly thicker veneer of cooperation and marginally more subtle Qatari support for the Muslim Brotherhood.

Key fact

The advance of Isis has brought the GCC nations together in recent months

Source: MEED

You might also like...

Ajban financial close expected by third quarter

23 April 2024

TotalEnergies awards Marsa LNG contracts

23 April 2024

Neom tenders Oxagon health centre contract

23 April 2024

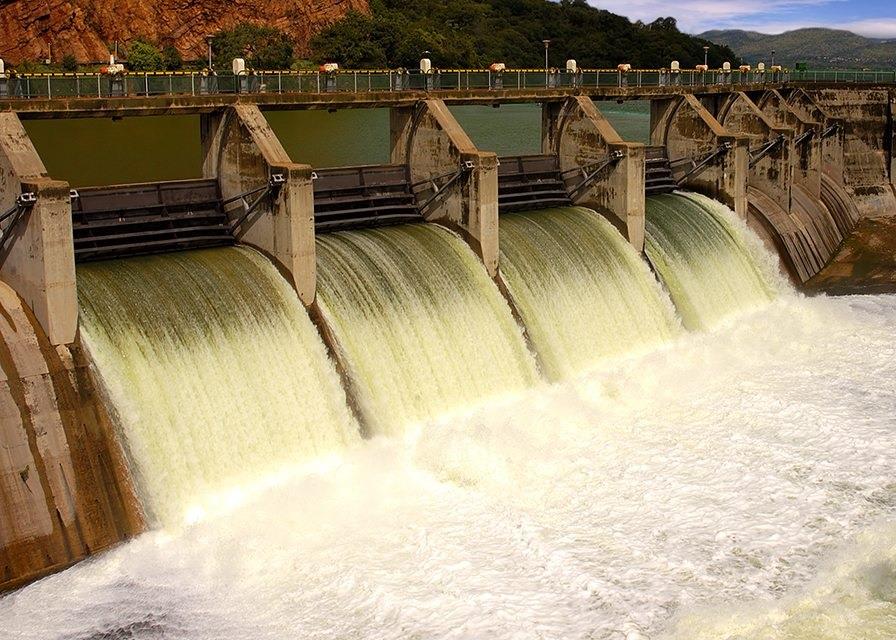

Neom hydro project moves to prequalification

23 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.