Second extension postpones elections until 2017

Lebanons parliament voted on 5 November on a motion to extend its term by two years and seven months, citing instability and a power vacuum in the country.

The deputies have failed to elect a president since Michel Suleiman resigned at the end of his six-year term in May. Without a sitting president, a prime minister cannot be nominated to form a new government after elections.

The inability to agree on a presidential candidate stems from the rivalry between the 8 March coalition, dominated by Shia militant group Hezbollah, and the 14 March coalition, led by Saad Hariris Future Movement. There are also structural issues caused by the clientelism and sectarianism of the political system.

We cant expect any improvement or a new president in the short term, said Sami Atallah, director of the Lebanese Centre for Policy Studies, after the vote. The political elite have failed to govern themselves since 2005.

Civil society groups have criticised the decision as undemocratic and preventing accountability.

Spillover from the Syrian civil war has destabilised the country, as well as the influx of more than a million refugees. This has put pressure on the economy, raising unemployment levels. Lebanons growth rate has fallen from 7 per cent in 2010 to 1.5 per cent in 2014, according to the Washington-based World Bank, with tourism and exports especially affected by regional instability.

The refugee crisis has exacerbated the weakness of the infrastructure, said Atallah. But really it has just exposed how vulnerable the infrastructure is, especially in the north and east.

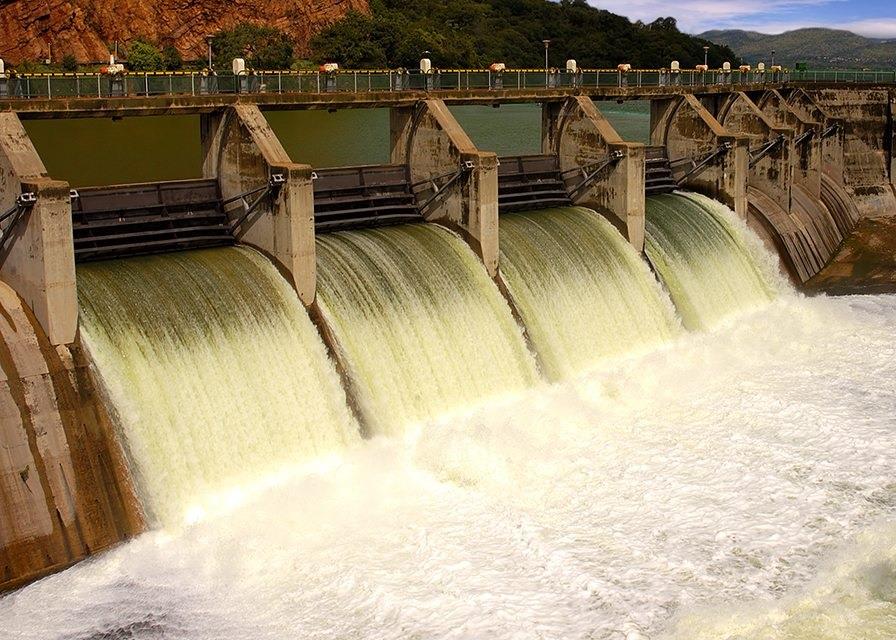

Lebanon has serious deficits in its power, water and communications networks, but few projects are moving forward. The Council for Development and Reconstruction, the governments executive body responsible for tendering major projects, declined to comment on their progress.

Advocates for a clear, accountable plan to deal with Lebanons economic problems are likely to be disappointed. The prospects for decisive policies or increased public investment are small due to political paralysis and the high level of public debt, at $60.5bn in 2013, which is about 141 per cent of GDP. Foreign direct investment (FDI) will not make up the difference, as it fell by 25 per cent in 2013.

But we still have a government and a state, however weak. Lebanon hasnt imploded, said Atallah.

You might also like...

Ajban financial close expected by third quarter

23 April 2024

TotalEnergies awards Marsa LNG contracts

23 April 2024

Neom tenders Oxagon health centre contract

23 April 2024

Neom hydro project moves to prequalification

23 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.