The announcement that an agreement is close to being reached over the debts of the troubled Saudi conglomerate is good news for private sector firms seeking funding

The announcement in September that a deal is close to being reached to settle the billions of dollars owed to Saudi banks by troubled family conglomerate the Saad Group could not have been better timed.

Local banks’ exposure to the Saad Group’s debts are estimated to be $3-7bn. For private companies in the kingdom, which have been effectively starved of credit for much of the past year as a result of the global financial crisis and its effect on bank lending, the news of a possible deal is an indication that a corner has been turned in the credit markets.

Key fact

Bank lending to the Saudi private sector fell by $1.6bn from December 2008 to July 2009

As if the regional economic contraction were not enough, the Saudi private sector has been reeling from financial problems afflicting prominent family-owned businesses. In May, the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (Sama), the central bank, froze the accounts of Maan al-Sanea, chairman of the Saad Group, amid revelations of billions of dollars of bad debts related to his company and to another major Saudi family-owned business, AH Algosaibi & Brothers.

Lending curtailed

The public feuding between these two large Saudi conglomerates, which together are estimated to owe banks $15.7bn, has had an impact on business confidence that extends beyond the banks most exposed to their losses.

With their investment portfolios dented by the financial crisis, and much greater provisioning needed on their balance sheets to account for deflated asset values, local and international banks have reined in their lending to the Saudi private sector, which until now had made up a sizeable proportion of their loan portfolios.

For example, Banque Saudi Fransi made SR120m ($32m) in provisions for loan losses between April and June this year, according to the Saudi stock exchange (Tadawul). This compares with SR46.1m in the first quarter of 2009, and SR10m in the second quarter of 2008.

Bank lending to the private sector in Saudi Arabia grew by just 3.6 per cent in the 12 months to July this year, according to figures from local bank Samba, its lowest rate of growth for more than six years.

Corporate credit, when it has been made selectively available, has been expensive: typically 250-300 basis points over the London interbank offered rate (Libor), compared with half that figure 12 months earlier.

Private sector firms have struggled to access finance despite the best efforts of Sama to ensure a flow of credit to companies. Sama has tried to encourage lending by reducing the reverse repo rate – the interest rate earned by a bank for lending money to Sama – from 2 per cent in January to 0.25 per cent by June. Yet the move has failed to encourage banks to lend.

The Saad/Algosaibi debt problems occurred at the same time as the global financial meltdown, making it difficult to work out what has been the principal cause of the lending drought. What is clear is that concerns over the level of Saudi corporate debts have had a material impact on banks’ risk strategies regarding loans to the private sector.

The banks’ risk aversion has been aggravated by high exposures to the private corporate sector, particularly family-owned businesses, where the practice of lending to influential families on the basis of their reputation has been the norm.

According to ratings agency Moody’s Investors Service’s Saudi Arabia Banking System Outlook, issued in September, such lending can give rise to a disproportionately high level of credit problems during economic downturns, and expose banks to risks.

“The clearest way to see the impact of the Saad debt problems is that bank lending has not grown in six of the past eight months, even though the issues of counterparty risk in the banking sector related to the global credit crisis were resolved by February or March,” says Paul Gamble, head of research at Riyadh-based Jadwa Investment.

Given that Saudi banks are well capitalised and not dependent on market funding, bank lending would have been expected to pick up in May or June.

“It is not because banks do not have money that they have not been lending,” says Gamble. “Deposits have shot up. It is because they are unwilling to lend and this is down to what has happened with the family businesses.”

Jadwa figures show that the value of outstanding bank loans to the private sector in July this year was SR6bn ($1.6bn) below its level of SR560bn at the end of December 2008, meaning that lending stands at a nine-year low.

This has had a direct impact on Saudi Arabia’s economy, which Jadwa forecasts will contract by 1 per cent this year. The firm expects that real private sector non-oil GDP will fall to a 10-year low of 2.3 per cent in 2009.

This has resulted in a series of projects being delayed or cancelled. Without funding, Saudi firms have had little option but to mothball or even scrap their investment plans.

Figures for the value of private projects on hold or cancelled had reached $77bn by mid June, from virtually zero in October 2008. Export-oriented manufacturers in particular are suffering, along with consumer-led sectors such as retail. For example, plans by the local Benaa al-Kawaed group to build two $50m mall complexes in Dammam and Jeddah have been on hold since early 2009.

The contraction in lending is also a by-product of the banks’ greater stringency in assessing risk, which has also been triggered in part by the emergence of corporate debt problems.

“There are now far more questions about the sectors that businesses are in, the way that business is conducted by family firms, and whether they are transparent enough,” says Said al-Shaikh, chief economist at National Commercial Bank and a member of the Majlis al-Shura (consultative council).

“Many Saudi companies have complex organisational structures, so banks are taking care to understand these and the partnerships they hold with each other, and elsewhere in the region. In the past, they did not pay that much attention to these issues.”

Risk assessment

These measures are underscored by Sama’s efforts to bolster risk procedures in line with Saudi Arabia’s commitments to the Basel II international banking standards. For example, all Saudi banks are now required to provide probability of default and loss-given default data for their corporate customers.

The tangible improvement in sentiment that the anticipated Saad debt deal has delivered – involving a commitment by Saudi banks with exposure to Saad Group to take about a 15 per cent reduction in the money owed to them as well as guarantees by Saad to repay SR9.7bn to local banks – may soon start to register in the real economy.

“The recent deal will help restore confidence and we should see some recovery in lending to the private sector, starting in October,” says Gamble. “The conditions are there.”

But a sustained recovery may take more than a deal with local banks. According to Howard Handy, chief economist at Samba Group, the outlook for the private sector depends largely on the return of international banks to the Saudi corporate debt market.

“We should see some recovery in lending to the private sector, starting in October”

Paul Gamble, head of research, Jadwa

Private investment will remain constrained until credit flows show a sustained increase. “With their predominantly short-term deposit bases, local banks have been hard-pressed to provide enough long-term funds to large infrastructure projects,” says Handy. “The return of international banks would help to provide a larger and longer-term capital pool.”

Increased government investment should also help the private sector. “The central bank has done pretty much everything in its power to improve liquidity in the financial system, while public investment has surged by $85bn since January,” says Handy. “This has helped shore up confidence in the economy and has obviously been a boon to private contractors.”

Confidence has yet to translate into increased private sector investment, and the value of private projects on hold continues to rise, albeit at a slower rate than previously.

But even if Saudi companies have already written off this year as a lost cause, they hope to see recovery beginning in 2010.

“They will gradually start to feel the recovery coming in, giving them more assurance in pursuing expansion plans,” says Al-Shaikh. “They are also tracking what is happening globally and are seeing that the worst is behind them.”

Much is expected of the Saad debt deal, but no single event is likely to trigger a surge in business confidence in the kingdom.

“It is more about things not happening,” says Gamble. “The longer we go without bad news, the more it helps.”

You might also like...

Ajban financial close expected by third quarter

23 April 2024

TotalEnergies awards Marsa LNG contracts

23 April 2024

Neom tenders Oxagon health centre contract

23 April 2024

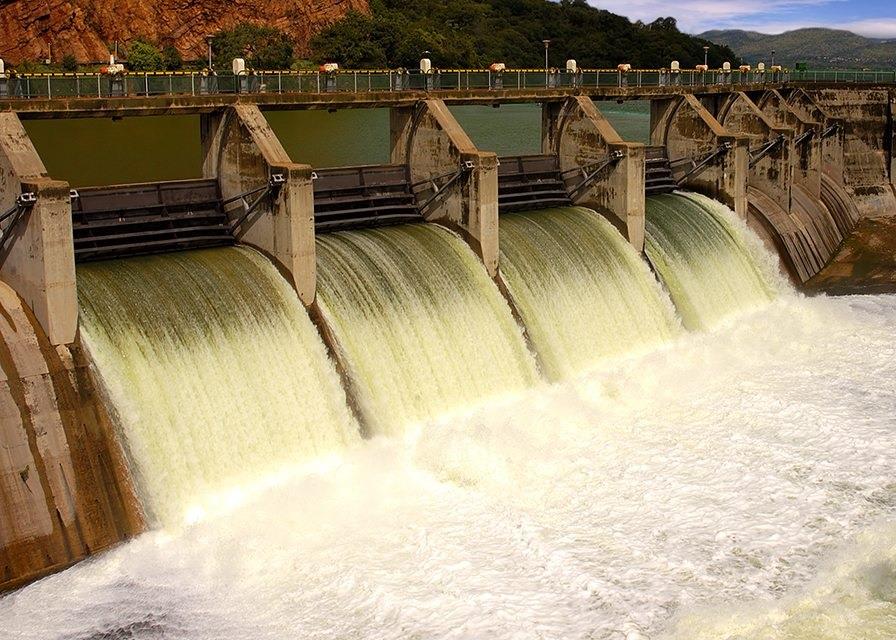

Neom hydro project moves to prequalification

23 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.