The $11bn petrochemicals project is finally expected to turn a profit in 2013, but spiralling costs and construction delays have left their mark

More than a decade ago, a group of Saudi engineers and entrepreneurs had a brainwave. If they could gain access to cheap butane, a by-product of petroleum production, they could create an entirely new downstream petrochemicals industry and generate greater value from the kingdom’s vast hydrocarbon resources. It was a laudable aim, but achieving it would prove more difficult than anyone imagined in 2001.

Profit forecasts have been downgraded … as a result of Saudi Kayan’s … operational issues

The idea behind the Saudi Kayan petrochemicals project was small, but it had huge goals. It aimed to diversify the petrochemicals industry, meet the kingdom’s desperate need for job creation and lay the groundwork for the development of new downstream industries. All this was to come from a project with an initial estimated cost of just $300m.

In the years since, Saudi Kayan’s budget has swelled to $10bn, construction has been delayed, bills have overrun to take development costs to about $12bn and profits have remained elusive. In the second quarter of 2012, the firm made a loss of $87m, one of its biggest to date. The project is only expected to start operating at full capacity and turn a profit in 2013.

Slow progress at Saudi Kayan

Saudi Kayan was the brainchild of the local Project Management & Development Company (PMD). In 2001, it secured a site at Jubail for the development of a petrochemicals complex and, within two years, had agreed a butane and ethane feedstock allocation from Saudi Aramco. It was among the first feedstock allocations made by the state oil firm and the first to the private sector – a major coup for PMD.

But progress on the scheme slowed considerably to 2006, during which time PMD tried in vain to attract a foreign petrochemicals firm as a joint venture partner on the project. In the end, it was left to state-owned Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (Sabic) to take a 35 per cent stake and effective control of the project. “When Sabic took control of the project they were really a white knight for the whole idea,” says one source who has been involved in the scheme.

By October 2005, PMD had made progress on appointing a project manager and raising funds through a private placement: the company was reluctant to provide any direct sponsor support itself. But changes in the project scope meant that within a year, the estimated cost of the Saudi Kayan scheme had spiralled to $6bn.

“The gas allocation changed and then the project changed from being an amines plant to including polyethylene and polypropylene and other downstream products,” says one source who was close to PMD at the time.

It marked a turning point for the project. From then on, costs spiralled further out of control as the region’s overheating engineering, procurement and construction market pushed the development budget to about $10bn.

“This is the sad part about it,” says the source close to PMD. Another UAE-based source who worked on the development of the project adds: “Projects built at the height of the boom will always be less profitable than ones built either side of it.”

Sabic again came to the rescue, managing to close a remarkable $10bn financing deal in late 2008, just as the credit crunch was turning into a full-blown financial crisis. That deal raised $6bn of debt, with the bank tranche priced at 50 basis points above the London interbank offered rate (Libor), rising to 75 basis points above Libor.

It wasn’t enough. In mid-2010, Sabic held talks with banks to determine how to fund a $2.4bn cost overrun at the Kayan project. Sabic said it gave Saudi Kayan a SR4.5bn ($1.2bn) shareholder loan in August 2010 to fund part of the rising costs of the project.

Saudi Kayan shareholder dividends

It is not just debt finance that has failed to progress smoothly for Saudi Kayan. In 2007, the company listed on the Saudi Stock Exchange (Tadawul) in a SR6.75bn ($1.8bn) initial public offering (IPO), at the time Saudi’s largest, with shares offered at par value, or SR10, each. Par value IPOs are often a condition of getting gas allocations from the government: by forcing companies who benefit from cheap feedstock to list, Riyadh aims to pass on the country’s hydrocarbon wealth to the wider population.

The IPO was more than four times oversubscribed as investors clamoured for what was widely expected to be a one-way bet. However, the company has not yet paid a dividend to shareholders and its share price was only about SR13 on 25 September this year, although it has risen to more than SR20 at several points since listing.

“Increased project costs and the delay in reaching full operating rates will limit Saudi Kayan’s ability to pay dividends in the medium term,” says Iyad Ghulam, an equity analyst at the local NCB Capital. Cost overruns and delays in the project are all to the detriment of those who participated in the IPO, mostly retail investors.

Investors in Western markets are more accustomed to mercurial share prices and understand that investments in greenfield projects carry a greater degree of risk – particularly surrounding project delays or cost overruns. For the Capital Market Authority (CMA), however, which regulates the kingdom’s stock exchange, Saudi Kayan was an embarrassment. Because of this, coupled with several other cases of investors not getting the returns they expected, the CMA is putting listing applications under even greater scrutiny and is determined to not let history repeat itself.

“The CMA will not allow a company to IPO before it has the debt financing in place ever again,” says one investment banker who advises on listings in the kingdom.

Operating rates

As 2012 comes to an end, shareholders may finally have reason to be cheerful. Ghulam says he expects Saudi Kayan to report a net profit in the fourth quarter of 2012, and analysts broadly expect 2013 to be the project’s first profitable year. While this is positive, profit forecasts have been downgraded for next year as a result of Saudi Kayan’s continued operational issues. “Kayan’s profitability and ability to repay its debt depend on the improvement in the operating rates,” says Ghulam. “We expect the company to reach the full operating rates towards the end of 2013.”

The project is currently estimated to be operating at about 70-75 per cent of capacity. In the first half, operating rates were thought to be closer to 60-70 per cent.

Saudi Kayan said its second quarter loss, its biggest so far, was due to the decline in prices of its products and increase in the cost of sales. Revenue was also affected, as sales in the second quarter came from inventory produced in the first quarter, when feedstock prices were high. Butane, which makes up about 80 per cent of its feedstock, is sold to the company at a discount from market prices, meaning that although it can be more competitive than its rivals, it is still impacted by rising prices.

One banker who has worked on the project counters that as prices rise, Saudi Kayan actually becomes more competitive, as the discount on the butane is greater. Regardless, the arrangement is in contrast with other projects in the kingdom. Gas feedstock is sold at a fixed price, meaning other industrial projects with a gas feedstock are completely insulated from rising prices.

Saudi Kayan’s debt repayments

Once Saudi Kayan begins turning a profit, it will need to turn its attention to deleveraging. At the end of the second quarter, the company’s debt-to-equity ratio was almost 200 per cent. Just paying the interest and accounting for losses over the rest of the year will continue to erode shareholder value. “We expect them to be profitable in 2013, but it will probably not be a huge money spinner,” says one analyst covering the petrochemicals sector.

Perhaps one of the toughest challenges ahead for Saudi Kayan will be managing its debt repayments. Now the project is almost fully operational, costs cannot increase much further and no additional delays are expected.

In part, the Saudi Kayan project has been a victim of circumstances far beyond its control. Had it been built a few years earlier, or even a few years later, the project’s economics would have benefited from significantly cheaper construction costs. As it ramps up operations, the company should start to recover ground lost to delays and rising costs. But it may struggle to ever completely make up for them.

Key fact

At the end of the second quarter of 2012, Saudi Kayan’s debt-to-equity ratio stood at 200 per cent

Source: MEED

You might also like...

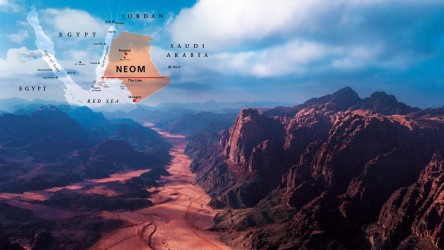

Neom seeks to raise funds in $1.3bn sukuk sale

19 April 2024

Saudi firm advances Neutral Zone real estate plans

19 April 2024

Algeria signs oil deal with Swedish company

19 April 2024

Masdar and Etihad plan pumped hydro project

19 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.