GCC states are reviving plans for a single currency, but meeting convergence criteria is posing problems.

The GCC single currency has a credibility problem. The official 2010 deadline has looked unachievable for so long that many economists doubt whether the project will ever happen.

So the decision last week by five of the six GCC central bank governors to set up a monetary council was an important step in restoring some certainty to the project.

At the same time, they acknowledged that the 2010 deadline was unrealistic. Instead, Sheikh Abdullah bin Saud al-Thani, governor of Qatar Central Bank, said after the Doha meeting that it was likely the GCC would only establish the council by 2010.

The launch of the monetary council, which in time will become the central bank of the GCC, is a vital step in creating a single currency, akin to the European Monetary Institute, which later became the European Central Bank.

Convergence criteria

The announcement is the first sign of progress on monetary union in months and is an important development. According to Standard Chartered Bank, installing the proper institutions for monetary union is the most important issue the governments can address at this point.

But some observers are still not convinced. “It is probably not much more than window dressing,” says one economist. “I am sceptical about a single currency. I think it will be delayed indefinitely.”

The plan for a nascent GCC central bank still has to be approved by finance ministers in September before it can proceed. If it does go ahead, it will join a select group of currency unions. The euro area is the most prominent, but others include the CFA franc zones in West and Central Africa and the East Caribbean dollar.

But there are many more hurdles to overcome before a GCC currency joins them, and some problems are unlikely to be resolved quickly.

The governor of the Central Bank of Oman did not attend the meeting as Muscat has pulled out of the project. No one expects it to rejoin before a currency is launched, and there is a small but real chance that other countries might go their own way as well. Smaller, practical issues such as whose image will appear on the coins and notes, and where a central bank will be located, will provide plenty of scope for debate.

The most significant problems concern the convergence criteria, specifically inflation. When the GCC decided to set up a single currency, it looked at the most recent successful example, the euro, and simply copied its convergence criteria.

As a result, each country has vowed to ensure its budget deficit is lower than 3 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), and that its public debt is less than 60 per cent of GDP.

They must also have foreign exchange reserves to cover at least four months of imports and ensure that interest rates are within two percentage points of the average of the lowest three countries’ rates. The last of these is easily achievable as long as they maintain their pegs to the dollar or, in Kuwait’s case, a currency basket dominated by the dollar, as their interest rates are virtually the same. Similarly, the huge budget surpluses they are running mean the requirements on budget deficits, public debt and foreign exchange reserves are no problem.

Of course, if oil prices fall, it could be difficult for some to meet the criteria on debt or budget deficits. From 1998 to 2002, Qatar’s government debt was 60.2 per cent of GDP, while Saudi Arabia’s was 96.7 per cent. A return to those levels would make both countries ineligible for the single currency.

Currently, the main sticking point comes with the final criterion. Inflation can be no higher than two percentage points above the average for all the states, and there is little prospect of the countries meeting this target. Current rates range from a low of 6.2 per cent in Bahrain to a high of 14.75 per cent in Qatar.

“We are all worried about the upturn of inflation at the moment,” says Robert Parker, vice-chairman of asset management at Credit Suisse. “If you look at inflation in a number of emerging markets, the numbers are getting quite alarming. We are seeing a number of countries with inflation well into double digits.”

On the basis of the 2007 inflation figures, the only country within two percentage points of the average is Oman. Even if you exclude Muscat and take an average across the five remaining countries, none of them qualify.

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) projections of inflation for 2008 are slightly more hopeful for the GCC. Only Qatar and Bahrain would miss out, although that is based on the optimistic assumption that the UAE’s inflation rate will fall this year.

Of course, figures can be fudged. Qatar has suggested that instead of using the typical headline inflation rate, the GCC should use core inflation, which excludes fast-rising rental prices, as the basis for the calculations.

This could add to the concerns of some over the credibility of government figures.

“The time lags in which you actually get official inflation figures are a real concern because you just don’t know what is going on, so how can you judge whether a policy is responding appropriately given how inflation is rising,” says Brian Coulton, head of global economics in the sovereigns group at credit ratings agency Fitch Ratings.

With or without official data, the most likely scenario is for inflation rates to rise even further in the short term. “I think they are going to converge around a high inflation rate,” says James Reeve, senior economist at Saudi bank Samba.

Even if that happens, inflation will remain a problem. “High and rising inflation is typically associated with more volatile inflation and that in turn is associated with more volatile economic cycles,” says Coulton.

Much of the blame for high inflation has been placed on the dollar pegs. With that in mind, some economists now expect the GCC to try a different policy for a single currency.

“I think the economic arguments are becoming more compelling for a break from the dollar peg,” says Reeve.

“A more robust, long-lasting solution would be a currency basket,” says Mustaz Khan, economist at Citi.

Concerns about inflation and dollar pegs aside, the GCC economies are all moving in the same direction. Current account surpluses have been rising and the level of government debt has been falling. Their economies are likely to line up even more closely if tax rates are unified, as has been suggested by Doha. “We are seeing convergence within the Gulf region,” says Parker.

Khan says the latest move by the central bank governors indicates they are dealing with the underlying issues to ensure this continues. “They are going to use this as a way to create discipline among their members,” he says.

Further moves will be made in the coming months to make a single currency more likely, including standardising data for inflation and other figures among all member states, he adds.

Political will

Ultimately, the problem could be that the criteria themselves are unsuitable, and while they worked well for European countries, the GCC needs to adapt them more.

“If they are serious about these criteria, they will have to customise them,” says Khan. “It is unreasonable to use exactly the same measure and figures for convergence as the EU.”

Agreeing on any new criteria will take even more time, delaying the project even further. Already, economists in the region expect the single currency to be brought in five years late at best.

But while some of the momentum has been lost, the project itself is likely to continue. The economic case for doing so is straightforward. A common currency will benefit the economies by removing the cost of foreign exchange on trade.

The trade-off is an end to the ability of governments to have their own monetary and exchange-rate policies. Countries will also be more exposed to macroeconomic problems in their neighbours.

But it is the political backing, rather than any economic rationale for it, that remains the main reason to believe it will happen. Despite the difficulties, notably around inflation, Reeve says: “I think they will hold the line.”

You might also like...

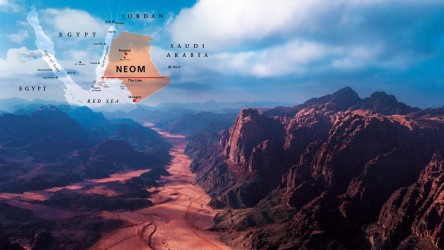

Neom seeks to raise funds in $1.3bn sukuk sale

19 April 2024

Saudi firm advances Neutral Zone real estate plans

19 April 2024

Algeria signs oil deal with Swedish company

19 April 2024

Masdar and Etihad plan pumped hydro project

19 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.