ConocoPhillips’ withdrawal from the Gulf could affect the future direction of the oil and gas sector, as local and international firms may be wary of striking up new partnerships

IN NUMBERS

50 per cent: Percentage of the Gulf’s natural gas deposits believed to consist of sour gas

93 billion cm/y: Non-associated gas processing capacity Aramco aims to raise by 2015

63 trillion cubic feet: The size of Kuwait’s natural gas reserves in 2010

cm/y=Cubic metres a year. Source: MEED

Projects in Saudi Arabia and the UAE were thrown into disarray earlier this year, following the decision of a US oil major to walk away from two multibillion-dollar schemes. The move throws into question the future of international oil companies (IOCs) in the Gulf.

Abu Dhabi will have to rebuild the financial case for Shah to bring in another IOC and … take on more of the risk

In April, MEED revealed ConocoPhillips had ended its participation in the $10bn Yanbu refinery development in Saudi Arabia – a 50:50 joint venture with energy giant Saudi Aramco. The same month, the debt-ridden firm quit the $10bn Shah gas project. That scheme was a joint development with Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc) in the UAE.

This decision could have far-reaching implications for similar joint venture schemes in the Gulf, making both sides more cautious about entering into partnerships. In the case of ConocoPhillips, Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia must now find suitable technically skilled partners for their projects, or push on with them alone.

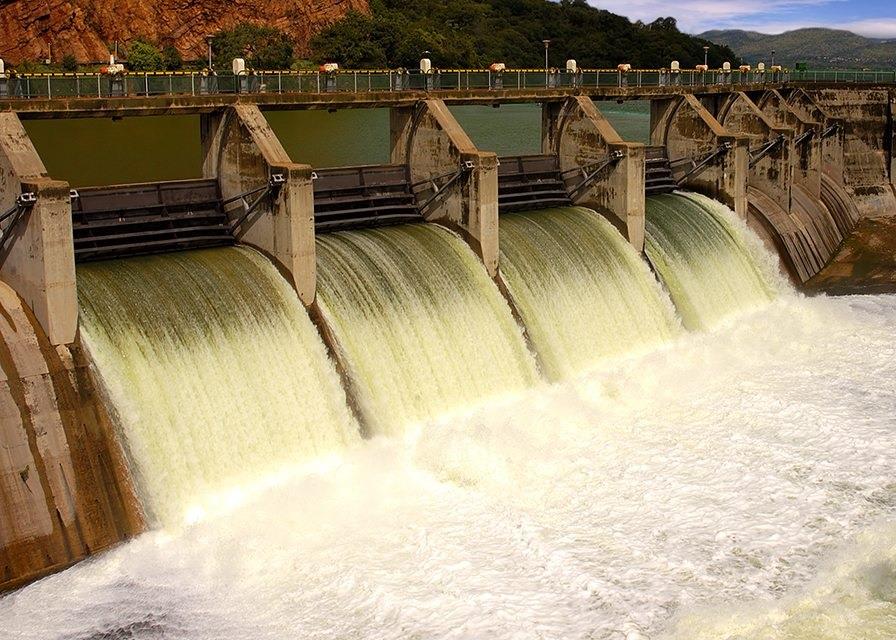

New sources of oil and gas in the UAE

Saudi Aramco has since stated it will build the 400,000 barrel-a-day refinery on its own. It approached several IOCs to replace ConocoPhillips in May, but decided to develop the scheme itself to prevent major delays.

For its part, Adnoc will have to find a new partner quickly, having waited more than a year while ConocoPhillips delayed making a final investment decision. Going it alone is not an option, as the Shah project is technically challenging with the gas produced containing a high proportion of sulphur, so IOC expertise is vital.

It is likely that [ConocoPhillips] will be passed over for future deals. It won’t be easy for them to get back in

Justin Dargin, Harvard University

The Middle East’s gas has tended to come from associated oil and gas fields, where the infrastructure is already in place to extract oil. Producing gas, therefore, adds little to the cost, says Justin Dargin, research fellow at the Dubai Initiative at the US’ Harvard University.

Sour gas – natural gas that contains high levels of toxic hydrogen sulphide – is estimated to account for more than 50 per cent of the Gulf’s natural gas deposits. Abu Dhabi’s Shah field, containing nearly 30 per cent hydrogen sulphide, is one of the largest in the region.

“From most oil fields, 5-8 per cent is typically considered sour, but the Shah field is unassociated and its gas is very sour, containing some 20 to 30 per cent sulphur,” says Dargin.

| ConocoPhillips in the Gulf | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Project | Location | Stake % | Value ($bn) |

| UAE | Shah Gas Development | Abu Dhabi | 50 | 11.2 |

| Qatar | Qatargas 3 & 4 (LNG train 6 & 7, onshore and offshore) | Ras Laffan | 15 | 4 |

| Qatar | Golden Pass LNG | US | 30 | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | Yanbu Export Refinery | Yanbu | 50 | 9 |

| LNG=Liquefied natural gas; Source: MEED Projects | ||||

The Gulf’s current gas shortfall has compelled regional national oil firms to reconsider using sour gas, previously deemed unsuitable for downstream industries. Delaying the Shah project will affect the emirate’s domestic supply strategy. Its gas supply/demand balance is already tight.

Adnoc and ConocoPhillips planned to produce 1 billion cubic feet a day (cf/d) of raw gas, yielding 540 million cf/d of processed gas for Adnoc’s distribution network. The emirate had previously worked with the US’ ExxonMobil on the offshore Upper Zakum field. It also partnered UK/Dutch Shell on the Rumaitha field development and the US’ Occidental Petroleum on the offshore Ramhan field, among others.

Abu Dhabi’s decision to opt for ConocoPhillips to develop the Shah field was at first considered an astute move. A new entrant to the emirate, ConocoPhillips was hoping to make its mark with the Shah project, in a country where its profile had been relatively low.

It took the company a year to sign the joint-venture agreement after winning the contract in July 2008. The firm was then careful not to commit to a final investment decision, waiting until 2010, once it had evaluated engineering, procurement and construction bids.

“[The decision to quit] was fundamentally about economics,” says Dargin.

Abu Dhabi will have to rebuild the financial case for Shah to bring in another IOC and may be forced to take on much more of the risk and cost. Any new partner is expected to demand significantly improved returns from the project.

Domestic gas pricing in the UAE at $1 a million BTU falls well below international rates. It would be unfeasible to develop such a technically complex field based on these prices.

Tough times for oil companies in the Gulf

It is not only US energy firms that are finding the going tough in the Gulf. On 15 June, Saudi Aramco announced that Luksar, a joint venture with Russia’s state-owned Lukoil, had relinquished 90 per cent of its gas exploration block in the kingdom’s Empty Quarter.

The joint venture abandoned most of its 29,900 square kilometre concession area in October 2009 and has decided not to pursue a second phase of exploration, Saudi Aramco said in its 2009 annual review.

Lukoil and Saudi Aramco signed the 40-year joint venture deal in 2004, one of five deals signed with IOCs to explore for gas in the vast Empty Quarter. The other agreements were inked with Shell, China’s Sinopec, Italy’s Eni and Spain’s Repsol.

Despite early optimism, the results have been disappointing. Lukoil has started drilling one of five appraisal wells in the block following two earlier discoveries.

In terms of developing new sources of gas, Saudi Arabia has been underwhelming. Talk of commercial finds in the Empty Quarter have been quickly dismissed by those in the gas community. Sources in the country say drilling will continue, but the mood is downbeat on the prospects of new discoveries in the kingdom as all the promising leads have already been drilled.

Saudi Aramco plans to raise non-associated gas processing capacity by almost 30 per cent to 93 billion cubic metres a year (cm/y) by 2015, from the current 64 billion cm/y, to meet rising demand from industry. But with few positive results from four years of exploration in the Empty Quarter, Riyadh may struggle to reach this target, which may hamper its attempts to diversify its economy.

Fostering oil and gas partnerships with Kuwait

One Gulf country that could potentially be about to bring in IOCs is Kuwait. This year state-run Kuwait Oil Company (KOC) agreed a $800m enhanced technical services agreement with Shell covering the development of the country’s northern gas fields.

KOC has been in talks with IOCs for the past four years, but until now had failed to reach an agreement. Shell became the first IOC to sign an enhanced services deal in Kuwait, with the energy major inking the contract at KOCs offices on 17 February.

Under the five-year deal, Shell will help KOC develop and manage its northern Jurassic gas fields, producing an undisclosed volume of non-associated gas. As with most of the region’s projects, the task is technically complex: The gas fields are deep, tight and sour.

Kuwait’s natural gas reserves stand at nearly 63 trillion cubic feet, most of which is associated with crude oil. In 2008, the country produced 12.8 billion cubic metres of gas. But the service agreements face considerable political opposition in the country, and senior IOC sources have previously told MEED they hold little hope of seeing them concluded. The Oil Ministry, KOC and KPC hold conflicting views on the role of IOCs, which could stall progress on the deal with Shell.

Kuwait is also planning to develop its heavy oil reserves. In April, KOC invited local and international firms to prequalify to build and operate temporary heavy oil-handling and processing facilities in the north of the country.

The production facilities will be used to test the viability of commercial production, with KOC leasing them from the winning contractor over an undefined period of time, likely to be five to 10 years. Permanent facilities will be built at a later date.

The tender comes as a further sign that Kuwait intends to develop technically complex heavy oil production facilities at its northern oil fields without assistance from IOCs. It had originally planned to develop the fields with the help of an IOC under its long-stalled Project Kuwait scheme, and signed a heads of agreement with the ExxonMobil to work on the fields in October 2007. But no progress has been made since.

According to one consultant, the state oil producer is rushing the project by using contractors with little expertise in heavy oil production rather than developing it using IOCs.

But using IOCs would bring the project under intense political scrutiny and cause significant delays, the source adds.

“Eventually [KOC] will have to bring in the IOCs,” he says. “But there is reluctance from the IOCs to get involved as they are not allowed to book reserves [profit from the oil being produced].”

Under Kuwait’s constitution it is prohibited for foreign companies to own any of the country’s natural resources, making the traditional production sharing agreements employed by IOCs impossible to use.

The pivotal role Kuwait’s parliament has played in blocking foreign participation in its oil sector, despite strong support for it within the Kuwait state oil company, is unlikely to be change soon, leaving the prospects for IOC involvement unlikely.

Testing working relationships in the Gulf

ConocoPhillips’ delays in making its final investment decision will have tested its relationship with Adnoc. It is hard to see how the US firm will be able to come back from this in the UAE, or in Saudi Arabia. ConocoPhillips may well find itself in a position where it is passed over for future projects by Abu Dhabi or Riyadh.

“This will be considered a loss of face. ConocoPhillips will have been thinking about its bottom line, but to the Saudis and the UAE their pullout will be considered a personal slight, at least in the short to medium term,” says Dargin.

“It is likely that [ConocoPhillips] will be passed over for future deals, if they do decide to bid for anything. It won’t be easy for them to get back in. In Kuwait, you are not dealing with an individual, but a body that purports to represent the country. So you have to deal with different interest groups. But in the UAE and Saudi, you are dealing with a hierarchical structure, so pulling out will not be so easy to forget,” he adds.

Abu Dhabi invested a lot of prestige in the Shah gas project and set itself an ambitious target, aiming for completion by 2015. Developing these resources is critical to Abu Dhabi’s economic development strategy as it seeks to cope with increasing demand for gas for power generation and industry.

ConocoPhillips’ revised strategy has made it willing to walk away from two of the most powerful oil companies in the region. It spent $850m on the two schemes, which it cannot recover after breaking the terms of its contracts by leaving at such a late stage in the projects’ development.

The decision may allow other majors to fill the void, but whether another IOC will want to invest huge sums in a region where fields are relatively mature and terms are tough remains a pressing question for Adnoc, Aramco and other Gulf oil companies.

You might also like...

Ajban financial close expected by third quarter

23 April 2024

TotalEnergies awards Marsa LNG contracts

23 April 2024

Neom tenders Oxagon health centre contract

23 April 2024

Neom hydro project moves to prequalification

23 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.