DUBAI ISLAMIC BANK (DIB) has lived undisturbed for 22 years in its own niche within the UAE's banking industry. A relatively poor performer in balance-sheet terms, DIB has been a reliable payer of dividends and was until this year the only purely Islamic bank in the country. However, the bank now faces the prospect of competition on its home turf from a new rival being established in Abu Dhabi

(see p16).

History and structure

DIB was founded in Dubai in 1975 during the oil boom which brought unprecedented wealth to the Gulf and created demand from local people for a bank that could invest their money in ways acceptable to Islamic law.

At the time it was seen as a novel and risky venture. The only other bank of the kind was the Islamic Development Bank, the multilateral development agency based in Jeddah.

'Most people said it would last six months and then close down, but it's lasted 22 years,' says Tarek Bin Hilal Lootah, a board director and nephew of businessman Saeed Lootah, who is DIB's founder, chairman and managing director. Five of the bank's nine directors are members of the Lootah family, which also has construction, real estate, trading and insurance interests in Dubai. The chairman owns a controlling interest in its shares.

DIB's main market is the UAE and neighbouring countries, though it provides financing and guarantees for trade transactions further afield, notably in the Indian subcontinent. In the local market, it provides corporate and retail banking services, with the exception of personal loans, and is an active financier of real-estate developments. Lootah says the bank is constantly developing new products, but declines to say more in detail.

The financing technique most important to DIB's earnings is murabaha, the bread and butter of Islamic banks since the 1970s. At the end of last year, about two-thirds of the bank's assets were in the form of murabaha receivables. In a murabaha deal, a bank buys goods on behalf of a client and receives payment for them in instalments. The bank makes its margin from a mark-up on the price of the goods which, in practice, tends to follow prevailing interest rates. Murabaha transactions tend to be for two years at most, though Lootah says that on real-estate deals, the tenor can be up to seven.

DIB is the sixth largest of the UAE's commercial banks, with assets of AED 7,109 million ($1,934 million) at the end of 1996. It has about 700 staff and nine branches and has a presence in six of the country's seven emirates. A branch in the tiny emirate of Umm Al-Qaiwain is due to be opened soon. In terms of profit growth, the bank has outrun the local banking industry as a whole in the last five years - net profits have risen by 234 per cent since 1992, compared to 86 per cent for local banks as a whole.

However, DIB is one of the least profitable of the UAE banks when measured by returns on its investments. In 1996, the return on equity was a mere 9.7 per cent compared to the unweighted average for local banks of 18 per cent; the return on assets was just 0.78 per cent against an average of 3.3 per cent.

'We are not as profitable as the traditional banks,' admits Lootah, but he adds that the bank has maintained a 10 per cent dividend to its shareholders for the last three years and has paid a rate of return to its depositors averaging 7 per cent.

Part of the reason the bank makes less money than its non-Islamic equivalents, Lootah says, is the shortage of profitable investments which conform with the bank's interpretation of Sharia.

'Traditional banks have more channels to invest. They can put it into any financial market for a week and get their money,' Lootah says.

Islamic banks have traditionally placed their surplus funds with Western banks for investment in commodity trading, and this has caused problems for some of them. DIB was one of nine Islamic banks which placed money with the Bank of Credit and Commerce International for murabaha investment and lost it when BCCI was shut down by regulators in 1991. DIB had AED 316 million ($86 million) invested with BCCI - most of this amount has been provisioned against since 1991, and the bank expects to get a third of its money back from BCCI's liquidators.

The Future

For 22 years DIB had the local Islamic market to itself, but this is about to change. The emirate of Abu Dhabi is sponsoring another Islamic bank which has already raised share capital of $272 million from private investors and a group of Abu Dhabi government institutions. This is likely to put some strain on DIB's earnings from its Abu Dhabi branch, which Lootah says is almost as large as its Dubai main branch. There is also talk of another Islamic bank being formed in Dubai. Lootah claims that DIB is not especially worried.

'It means that we are right, and we are proud that we were the first people to start this idea [of Islamic banking],' he says. 'Competition has disadvantages, but we can now see ourselves and see how well we are doing in the market. When you can find your disadvantage and solve it, this is an advantage.'

He is also upbeat about the entry of conventional banks into the Islamic market. Citibank has had an Islamic banking subsidiary up and running in Bahrain for a year, and other traditional banks are looking at ways into the industry in the Gulf.

Lootah suggests that DIB's main selling point is the strength of its religious credentials. 'Even if Citibank or any other bank opens a branch, there is still room in the market. And people may feel that this bank did not open to serve the Muslims. You cannot open a traditional bank with an Islamic section [just as] you can't be a priest and a bartender.' But he concedes that most Muslim depositors are pragmatists. 'Most people in the Muslim world, unfortunately, are not very Islamically-oriented. They will deal with Citibank. We can try to draw their attention, but at the end it is their decision.'

Nonetheless, the established Islamic banks are in a strong position to ward off competition from new entrants. 'We can market our products in a better way and make people realise that if we cannot provide the same service as other banks, we can provide a better and safer service.' He argues, for example, that risks are more fairly spread in an Islamic bank between shareholders and those depositors who hold investment accounts, because the returns paid to both are determined by the bank's profitability.

DIB prides itself on being conservative in its interpretation of the Sharia, and is wary of some new products, such as Islamic equity funds, which are gaining popularity in the industry but whose ethical acceptability is still being debated by scholars.

'We like to stay away from anything which could be questionable. In Islam, we have a law which says that the halal and haram [permissible and forbidden] are clear, but there are things between them which are not clear. It's better to try to stay away from unclear things,' Lootah says.

You might also like...

UAE rides high on non-oil boom

26 April 2024

Qiddiya evaluates multipurpose stadium bids

26 April 2024

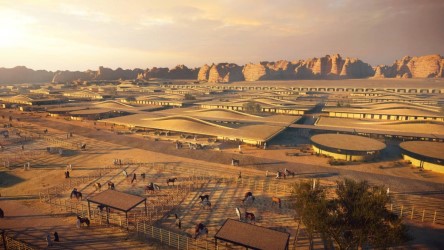

Al Ula seeks equestrian village interest

26 April 2024

Morocco seeks firms for 400MW wind schemes

26 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.