Despite a management reshuffle following an investigation into corruption, state energy firm Sonatrach has yet to boost gas supply in Algeria. Are shortsighted strategy and lack of investment to blame?

Oil & gas in numbers

40.6 billion: The amount in cubic feet Algeria produced of liquefied natural gas in September 2010

81 billion: Algeria’s production capacity of liquefied natural gas in cubic feet in September 2010

4.5 per cent: Expected fall in hydrocarbons export revenue in 2011, assuming 2010 oil prices

Source: MEED, Algeria Finance Ministry

The past year has been a torrid one for Algeria’s oil and gas sector. In mid-January, the government announced that state energy company Sonatrach was the subject of an investigation into corruption in the awarding of contracts, an inquiry that resulted in the removal of the company’s chief executive officer (CEO), Mohamed Meziane, three of its four vice-presidents and several other senior officials.

[Many] express concern about the state of mid-stream infrastructure as a result of long-term underinvestment

Samuel Ciszuk, IHS Energy

An interim management team was put in place, but the shadow of the investigations, led by the state security service, meant that contract awards in both the upstream and downstream sectors ground to a halt. In May, the energy minister, Chakib Khelil was replaced by Youcef Yousfi in a cabinet reshuffle, and a new team was appointed to lead the state oil and gas company. Nouredine Cherouati was named as Sonatrach CEO.

Slow gas activity in Algeria

With a new team in place, there were hopes the second half of 2010 would witness a resumption of oil and gas activity, but progress on major projects continued to be slow. In December, news emerged that the only Sonatrach vice-president yet to have been implicated by the investigations, the downstream chief and interim president Abdelhafid Feghouli, had been placed under judicial investigation. This raised the possibility of further delays to the implementation of a number of downstream projects over which he had presided.

Algeria’s midstream oil and gas business is in disarray. Its pipelines are more or less crumbling

Justin Dargin, international LNG consultant

Several key contracts expected to be awarded in 2010 are still to be signed. The government is still to put pen to paper on an agreement with France’s Total for an ethane cracker at Arzew, or with Almet, an international consortium, for a methanol plant. A scheme to build a new refinery at Tiaret is yet to get off the ground five years after it was first drawn up. Spain’s Repsol is still awaiting approval of development plans for the promising Reggane North gas field, despite having submitted them in 2009.

Still more troubling, the disruption at the heart of Sonatrach has been followed by a decline in the country’s gas exports. According to Waterborne, an energy consultancy, Algeria produced just 40.6 billion cubic feet of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in September 2010, barely 50 per cent of its 81 billion cubic-foot capacity.

| Algeria gas reserves (Trillion cubic metres) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | 1999 | 2008 | 2009 |

| 3.25 | 4.52 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Source: BP | |||

The severe underproduction in output can partly be explained by circumstantial factors. The Medgaz pipeline, which is set to transport 8bn cubic metres a year of gas to Spain when it begins full operations in 2011, was being tested during the summer months, and summer is also a favoured time for maintenance work to be carried out on the hydrocarbons network. But these elements cannot account for such an extreme fall in production. Two more fundamental forces are at work: a change in Algeria’s strategic direction, and the limitations of its gas production infrastructure.

The personnel changes at the head of the country’s energy sector have brought a turnaround in the approach to international gas marketing.

In 2008, Khelil took a decision that long-term gas contracts would no longer be signed, or renewed, and that they would instead be replaced by shorter-term contracts and spot sales. The idea was that in so doing, Algeria would be able to take advantage of surging international gas prices, which were reaching $15-20 a million BTU in some spot deals.

Reverse gas strategy in Algeria

Unfortunately, the decision to switch to short-term contracts coincided with the collapse of global energy demand and the discovery of commercial quantities of shale gas in the US, which together resulted in a drop in gas prices to about $4 a million BTU. Yousfi is now trying to reverse the strategy of his predecessor, moving away from spot deals towards long-term deals.

There is some logic to such a policy. Some more conservative members of Algeria’s ruling elite are keen to see the country’s resources conserved for the benefit of future generations. With lower gas prices this argument becomes all the more persuasive, but there are also downsides to such a policy, not least the way it has been implemented.

In recent months, Algeria has been foregoing spot deals on the UK market at more than $8 a million BTU despite holding the rights to LNG import capacity at UK’s Isle of Grain regasification terminal. A long-term strategy to move away from spot deals may well make sense, but in the meantime opportunities to make money are being missed. “Algeria put itself in the weakest position going into the economic crisis. By not taking advantage of the short-term sales now on offer, they are possibly doing so again,” says Samuel Ciszuk, senior Middle East analyst at IHS Energy.

The strategic reorientation also has implications for Algeria’s global position. If the government is determined to wait for a recovery in gas prices before it starts to increase its exports then it could have a long wait on its hands. Meanwhile other global players are ramping up their LNG production.

Qatar has recently completed the construction of new liquefaction trains that took the country’s LNG capacity to 77 million tonnes a year. Qatar is quickly building a dominant market position, based on the emirate’s cheap gas and the economies of scale it can leverage by using the world’s largest LNG trains and tankers. If all goes to plan, towards the end of the coming decade Australia will also become a major global LNG producer, threatening Algeria’s market share still further.

Poor gas infrastructure in Algeria

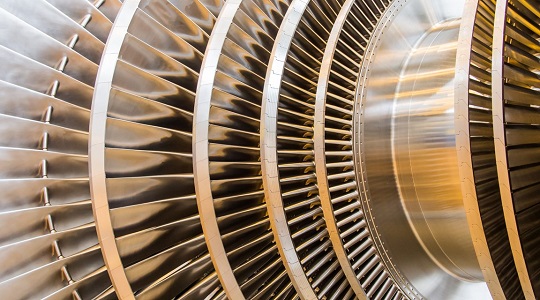

As Algeria’s competitors continue to invest billions of dollars building state-of-the-art facilities, important parts of Algeria’s hydrocarbons infrastructure are being neglected.

The government has successfully moved forward with the Medgaz pipeline, and new LNG trains are due to come on stream at Skikda and Arzew in 2013-14. When it comes to maintaining the domestic pipeline infrastructure on which supply to these terminals relies, however, the performance has been poor. A programme to rehabilitate a national network of oil and gas pipelines – substantial parts of which are as much as 40 years old – has been substantially downsized, leading to an increased incidence of maintenance outages.

“There are increasing reports of operational problems,” says Ciszuk. “A lot of people are expressing concerns about the state of mid-stream infrastructure as a result of long-term underinvestment. A fall in LNG production to 50 per cent of capacity must signify that there are some really big problems. Algeria may find itself increasingly unable to deliver what they are producing.”

“Algeria’s midstream oil and gas business is in disarray,” says Justin Dargin, an international LNG consultant. “Its pipelines are more or less crumbling.”

There are also problems further upstream. A combination of rapidly rising domestic demand and a slowdown in the licensing of upstream acreage. Not only has the Reggane North development fallen behind schedule, but the momentum of the country’s licensing rounds has also been lost.

The most recent two rounds resulted in barely a quarter of the acreage on offer being licensed. There is little optimism that the next round, on which bids are due in February, will be any more successful.

“There have been signs recently that the government realises there are systemic problems, but there has been no attempt to reverse the trend,” says Ciszuk. “There continues to be a push for tighter terms without showing any understanding that this course of action could cause problems. Expectations for the next bid round are very low. I’ve not heard anybody singing its praises, or anyone who is very excited about what’s on offer.”

Already there are signs that Algeria is losing its share of global gas sales. Having fluctuated at about 86 billion cubic metres a year (cm/y) between 1999-2008, Algeria’s gas output dropped 4.9 per cent in 2009 to 81.4 billion cm/y. Over the same 10-year period, its share of worldwide gas production fell from 3.7 per cent to 2.7 per cent.

There is little sign of this trend being reversed in the near future. At the end of October, the Finance Ministry announced that it expects revenue from hydrocarbons exports to fall by 4.5 per cent in 2011, assuming the same average oil price as in 2010. Oil and gas output is also set to fall in 2011 by 0.8 per cent, according to Karim Djoudi, the finance minister.

Economic implications for Algeria

“There’s a resignation to the fact that they can’t worry about market share when they don’t have the gas,” says Hakim Darbouche, a specialist in Algeria at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “A fall in market share for Algeria is inevitability now, at least for the next six-seven years until new gas reserves come on stream from the southwest, so they have to make sure that they get the best price they can for every molecule.”

The wait for new gas to come on stream could mean that when the new LNG terminals at Skikda and Arzew are completed by 2013-14 as planned, Algeria may find itself in a position where it is unable to meet all the calls on its gas. “Given Sonatrach’s problems, filling the void of falling foreign investment upstream will be tough for Algeria,” says Ciszuk. “It will be difficult to increase their exports in the future, and it is even questionable whether they have the gas for existing projects.”

This could have serious economic implications for a country that is reliant on oil and gas for 97.5 per cent of its export revenues.

“Oil and gas is a major part of Algeria’s budget,” says Dargin. “Some Gulf states could take the hit, but Algeria really can’t do that. I can’t imagine they’re happy about falling output. They have a vested interest in earning revenues.”

You might also like...

Morocco seeks firms for 400MW wind schemes

26 April 2024

Countries sign Iraq to Europe road agreement

26 April 2024

Jubail 4 and 6 bidders get more time

26 April 2024

Amiral cogen eyes financial close

26 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.