The development of mega hospitals shows no signs of slowing as primary and elderly care expands

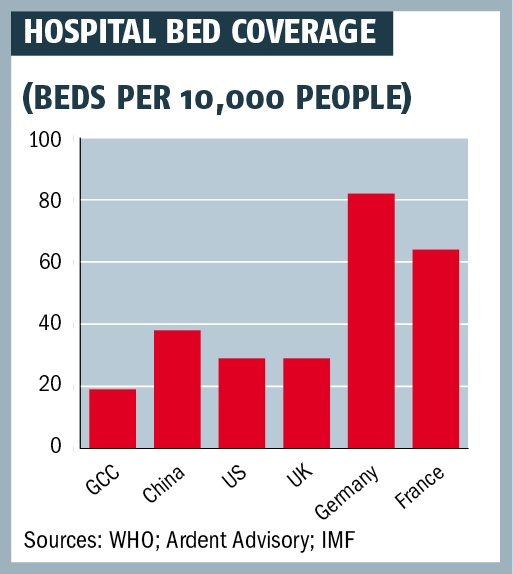

Hard figures tell the headline story: healthcare spending in the GCC is set to reach $133bn a year by 2018 and the regions governments are investing massively in new infrastructure. Some 37 major hospital projects are under way, at a cost of $28bn, and will provide a further 22,500 beds.

This will come on top of the 13,000 beds already added to Gulf health systems in 2009-13.

In 2014 alone, some $3.7bn-worth of health projects were completed and the projected total for 2015 is almost double that.

Private investors

Nor is this a purely public service affair. Increasingly, private sector investors see GCC healthcare as a promising growth area, attractive for both private equity investment and partnerships with government agencies.

Yet beyond the mega hospital projects and prestige ventures, the provision of healthcare is evolving in ways that will have a profound impact on both public service delivery and the role of the private sector in this key industry.

While there is a need for more specialist hospital facilities, to reduce the reliance on sending GCC nationals overseas for expert treatments, there is also a growing recognition of the need to focus on primary provision, to treat more patients at an early stage and provide advice on diet and exercise to tackle the lifestyle issues that have left Gulf nations with high rates of diabetes, heart disease and other illnesses of affluence.

Community healthcare

More extensive provision for healthcare in the community and at home is needed too, because at present many hospital beds are occupied by elderly people who do not need hospital-level medical care and could be looked after at home.

Technology effective use of resources, e-visits providing online medical advice and so on is another area of priority development and a market that is now valued at $2bn-3bn a year.

Some 37 major hospital projects are under way, at a cost of $28bn, and will provide a further 22,500 beds

The coverage provided by health services is also widening, as countries introduce insurance schemes and seek to provide better care for lower-income expatriate workers. And this means providing the necessary medical centres and hospital capacity.

The picture is further complicated by the development of facilities within the Gulf itself to cater for medical tourists: by 2020, the UAE hopes to be attracting 500,000 foreign visitors a year to undergo treatment.

In short, the Arabian healthcare industry is in a period not only of growth, but also of change: the type of services provided, the range of population these services aim to reach and the manner in which they are delivered and financed are all being transformed.

The development of new projects and services is necessarily a slow process in such a complex area. So while it is possible to make rough guesses about how much money might be spent on new developments in a single year, the more significant pointers are the big trends and the strategic plans devised by individual governments, which may be implemented over a period of years.

A major hospital project takes years to plan and design in detail, even before the process of construction can begin. It then has to be equipped and staffed.

Recruitment issues

The latter issue is a serious constraint, because GCC countries, many with small national populations, are highly reliant on the recruitment of expert staff from abroad. There is a shortage of GCC national medical staff, just as there are shortages of engineers, bankers, architects and many other specialist skilled roles.

Mobilising capital for the development of new facilities and services also poses problems, both in absolute financial terms and in matching the readiness of investors and banks to provide funding with the real pattern of demand.

For example, will GCC governments be able to draw investors into financing the provision of residential care facilities and at-home treatment services for the elderly?

Top hospitals are glamorous and their output is perhaps more easily managed; the provision of home support for older people is not so remunerative. It is also difficult to put an exact value on the benefit to hospitals of a health service caring for more pensioners at home

GCC governments and their specialist advisors and international partners do tend to think long-term about these issues and ways of measuring progress.

The year-by-year figures for investment may fluctuate and that in itself would hardly be surprising when the slump in global oil prices has had such a dramatic impact on Gulf nations income. But what is more significant are the long-term trends.

That certainly applies to the role of private sector funding for the GCC health sector overall. The private sectors share of healthcare funding in the GCC was 32 per cent in 2008 and 30 per cent in 2013, but it has only fluctuated marginally. It did not sink below 26 per cent and did not rise above 32 per cent. This pretty narrow range can be explained by local variations in economic conditions from year to year, but fundamentally there was no significant shift in the balance of expenditure between public and private sectors.

Medical tourists

The demand for healthcare is driven by two principle market elements: national GCC citizens and expatriates. But visitors coming from abroad for treatment are a significant, if still marginal, contributing factor; after all, they can actually help to render the development of specialist hospital facilities more viable in economic terms because they create an additional demand for services that might not otherwise be in full-time use.

A slowly growing number of Gulf countries are turning to insurance as a means of funding healthcare for their expatriate workers, especially those on lower incomes

The UAE has taken a deliberate decision to attract more medical tourists, by relaxing the visa rules that apply to such cases to reach its target of 500,000 medical tourists by 2020.

The core national market in each GCC state is distinguished by two key features: treatment is financed by governments that understandably regard the wellbeing of their citizens as a priority and are prepared to spend heavily on catering for their needs; and secondly, nationals are resident over their full lifespan in their home countries and services therefore need to cater for this full range from antenatal care to paediatrics, routine services for adults and specialist services for the elderly.

The expatriate population is different, because among those in lower-income roles the proportion of those living in the GCC as single adults is high. In proportionate terms, there are fewer mothers, children and old people to look after. Moreover, the incomes of many expatriates are much lower than the average for locals.

Health insurance

For many years, GCC health systems have struggled to adequately cope with these twin realities, in economic terms at least. But insurance is emerging as a solution.

Nationals often benefit from care funded by the state, whereas a slowly growing number of Gulf countries are turning to insurance as a means of funding healthcare for their expatriate workers, especially those on lower incomes. (Expatriates higher up the income scale have often benefitted from remuneration packages that include health coverage anyway.)

For example, Abu Dhabi introduced compulsory health insurance for all residents back in 2008, while in 2014 Dubai introduced a requirement for all firms with more than 1,000 employees to provide medical cover for their staff, with smaller firms obliged to follow suit in 2016.

But Saudi Arabia had already become the first country to impose a requirement for health insurance in the private sector. Bahrain has operated a mandatory system for nationals since 2003, and similar arrangements are now planned for expatriates. In Kuwait, health insurance is a prerequisite requirement for foreigners applying for a residence permit. Oman has indicated that it too will impose an obligation to arrange health insurance for staff in the private sector.

Insurance has a direct impact on the type of facilities that are being built, particularly to cater for foreigners on lower incomes. In the UAE, legislation has driven the introduction of services to cater for all workers at a basic level designated as essential benefits. This will come into full effect in 2016.

Private investors are responding to the emergence of this new market at the lower end of the income scale. Last year, Dubai-based Aster DM Healthcare introduced a new brand, Access, which targets those on lower incomes and aims to provide no-frills, good-quality essential care, with user fees paid under the new mandatory insurance policies.

But while primary care centres and support for the elderly represent a growing element in the palette of health services that GCC states are developing, the development of major new hospitals is not slowing down. A $680m medical complex is being developed at Abu Dhabis Mohamed bin Zayed City, including a 400-bed hospital and housing for personnel, while an 838-bed hospital is planned for Sheikh Khalifa Medical City in Abu Dhabi city. This large new hospital will have specialist trauma, gynaecology and paediatrics departments.

Medical cities

Saudi Arabia is investing $4.3bn in the development of five new medical cities. King Khalid Medical City in Dammam ($1.2bn) will include an academic medical centre with 1,500 single-patient rooms, a 500-bed private community hospital, medical schools and hotels, while King Faisal Medical City ($1.1bn) in the Southern Province will offer 1,350 beds.

Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz Medical City in the northern region will have 1,000 beds, and a 500-bed complex is planned for Al-Jouf, also in the north. The King Fahd Medical City in Riyadh will be expanded, and Meccas King Abdullah Medical City will have 1,350 beds in three hospitals and 10 medical centres.

Kuwait has been developing eight new public hospitals, to increase total national bed provision to 11,000, while Oman is building the Sultan Qaboos Medical City in Muscat, which will include both a general hospital and specialist facilities for treating head and neck problems and paediatric cases, an organ transplant unit and rehabilitation facilities.

By 2020, the UAE hopes to be attracting 500,000 foreign visitors a year to undergo treatment

Source: MEED

You might also like...

TotalEnergies to acquire remaining 50% SapuraOMV stake

26 April 2024

Hyundai E&C breaks ground on Jafurah gas project

26 April 2024

Abu Dhabi signs air taxi deals

26 April 2024

Spanish developer to invest in Saudi housing

26 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.