In 10 years' time, it is likely that the number of mobile phone subscribers worldwide will overtake fixed line subscribers, according to projections by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)*. Many, if not most of those mobile subscribers will be using third generation technology, which will allow the phone to be used for a bewildering array of functions, including e-commerce, video, remote medical services and even karaoke. How widely this new technology will spread in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) will depend to a large extent on the extent to which governments allow private investors to control developments.

By the end of 1998, the ITU calculates there were 8.8 million mobile phone users in the MENA region. Of these, 3.5 million were in Turkey and 2.2 million in Israel. By 2000, the total is expected to increase to 14 million, including 5 million in Turkey and 3 million in Israel.

The fastest rates of growth will be recorded in those markets where competition has been introduced, notably Egypt and Morocco. Both examples have useful lessons for other Arab states.

Egypt in 1998 awarded two licences for$516 million each to the Egyptian Company for Mobile Services (MobiNil) and Misrfone groups. MobiNil's partners include France Telecom, Motorola of the US and the local Orascom Telecom. Misrfone's main investors are the UK/US Vodafone AirTouch and local partner Alkan. In the 18 months since the licences were awarded, the two operators have secured more than 600,000 subscribers, and MobiNil has become the most valuable stock listed on the Egyptian bourse. Both companies have found that pre-paid cards have accounted for a major part of their business.

The rapid growth of this new business has exposed deficiencies in the Egyptian regulatory framework, which are only now starting to be addressed by a newly appointed minister dedicated to modernisation of telecoms and information technology. The experience has shown how centralised telephone bureaucracies are incompatible with efficient, fast-evolving new mobile systems.

The ITU notes that: 'The responsibility for the packaging and pricing of mobile services in most countries is out of the hands of those who designed and built the service and in the hands of those who must sell it.' Finding out customer needs and acting quickly to satisfy them is difficult to achieve when state regulation is too heavy-handed.

Morocco seems to have absorbed some of these lessons in its approach to awarding a second GSM licence. The tender was handled by the independent regulator with the help of NM Rothschild, and set a new international benchmark for transparency and for the value of such licences. Morocco opted for a combination of the 'beauty pageant' - whereby bidders are ranked on technical merit - with the highest price. The winning consortium, led by Spain's Telefonica, came second to Orange in the technical evaluation, but still won because of its price of just over $1,000 million. The ITU reckons that the highest price will continue to be the preferred mechanism for awarding licences, but says including technical criteria also has its advantages, particularly given the way in which the technology is evolving. The high initial fee paid for the licence is obviously attractive to the government concerned, but the drawback is that such high initial costs for the operator will eventually be passed on to the customer.

The ITU recommends that regulators should licence as many mobile operators as theoretically possible and never award exclusive licences. 'These actions should help to ensure competition and bring lower prices, thereby enhancing access.'

Prospects for new mobile operating licences in the MENA region are not that encouraging, in the short term in particular. Opportunities are coming up in a number of the more difficult markets, but the big prize of a licence in Saudi Arabia is still some way off. The next licence to be awarded could well be in Algeria, where Orascom Telecom - part of the Egyptian MobiNil group - has been trying to negotiate a licence with the new regime of President Bouteflika. Tunisia is also considering inviting bids for a private GSM licence, and Syria and Yemen are gearing up to join the mobiles era in earnest.

In the Gulf, the state-controlled monopolies continue to hold sway. But change is in the air. The most significant new development has been the creation of the Saudi Telecommunications Company (STC), and the announcement of plans for its privatisation. Business executives accompanying US Commerce Secretary William Daley on his 16 October visit to Riyadh were told that STC was seriously considering the option of selling an equity stake to a strategic investor. Such a step would entail a radical opening-up of one of the largest regional markets, and would be likely to be emulated by other GCC states.

Privatisation of telephone corporations is also under way in Egypt and Morocco, although it is not yet clear if or at what stage strategic investors will be involved. Jordan is now deciding between two bids, both mysteriously priced at exactly $508 million, for a40 per cent stake in its fixed telephone line company.

* World Telecommunications Development Report, October 1999, ITU, Geneva

You might also like...

UAE rides high on non-oil boom

26 April 2024

Qiddiya evaluates multipurpose stadium bids

26 April 2024

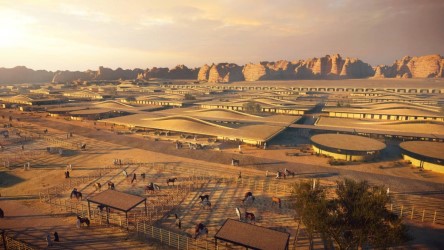

Al Ula seeks equestrian village interest

26 April 2024

Morocco seeks firms for 400MW wind schemes

26 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.