Over the past decade, healthcare services in the GCC have improved significantly, but undersupply continues to ail the sector. Population growth, increasing life expectancy, as well as a rising incidence of lifestyle diseases such as obesity and diabetes, are all driving escalating demand for healthcare services in the region.

According to statistics published by various GCC countries, average hospital bed capacity per 1,000 people was 1.9 in 2016, compared with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average of 4.7. Added to this challenge is the scarcity of local skilled and experienced physicians and nurses.

Against this backdrop, the cost of healthcare is climbing steadily. And the need to deploy the latest and most advanced technologies adds to the financial burden.

Historically, healthcare initiatives in the GCC have been primarily government owned and funded, with the public sector accounting for about 70 per cent of healthcare spending in the region, according to data from the World Health Organisation and Washington-based IMF. But to deal with the challenges facing the sector, the public and private sectors need to pool their resources and expertise.

Alternative approach

Public authorities in certain countries have limited financial resources and expertise and, as a result, have implemented public-private partnerships (PPPs).

Spain, for example, has a healthcare PPP known as the Alzira model, under which the private sector assumes responsibility for building, owning and operating facilities. The government pays a fixed annual fee and assumes ownership of the assets after a 20-year concession. The private sector is responsible for all the cost, but the government has to ensure a level of demand.

Turkey, on the other hand, operates a system in which the private player provides the design, construction works, financing, medical equipment and other services, but not the medical services. The Turkish Ministry of Health takes responsibility for providing health services and the project company receives periodic payments, including availability payments and service payments, throughout the concession term.

Similarly, in the UK, under the Private Finance Initiative, the National Health Service (NHS) has signed more than 100 PPP agreements, worth more than $18bn in total, since the early 1990s. These projects usually involve private funding to design, build and operate hospital buildings, including ancillary non-clinical services, such as cleaning and catering. However, the core services – clinical, medical and nursing services, including doctors and nurses – are provided by the NHS.

Comparison of PPP models across other geographies

| Egypt | Turkey | Spain | UK | India | |

| Contractual structure | Design-build-finance-operate-transfer | Design-build- finance-lease-transfer | Design-build-finance-operate-transfer | Build-own-operate-transfer | Design-build-finance-operate-transfer |

| Land | Provided by government | Provided by government | Provided by government | Provided by government | Provided by government |

| Concession term | 20 years | 25 years | 15-20 years | 25-30 years | 30 years |

| Clinical services provider | Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health | Private partner | Ministry of Health | Private partner |

| Non-clinical services operator | Private partner | Private partner | Private partner | Private sector | Private partner |

| Payment structure | Availability-based and services-based payment | Availability-based and services-based payment | Capitation fee (fixed annual sum per local inhabitant) | Availability-based and facility management fee | Capacity payment and viability grant funding |

| Government incentives | Ministry of Health guarantees minimum 70 per cent occupancy ratio for service payments | - Grant funding - Fast track approval

- Assistance in procuring utilities |

Financial shortfall

Utilising a PPP mechanism to fund social infrastructure is not a new concept in the GCC, but when it comes to the healthcare sector, adoption is nascent. Overall activity remains confined to private sector engagement through management or design-and-build contracts. But regional governments have recognised the need for PPPs to bridge the shortfall in financing.

Private players are being incentivised through PPPs to invest in and manage operations, while the public sector acts as the regulator. GCC countries are in the process of implementing reforms to existing PPP laws, or drafting entirely new laws, to map out the legal framework for healthcare PPP projects.

Saudi Arabia’s Health Ministry has been working to formulate a policy framework under which the ministry will transition to a regulator from its current role as a service provider. The ministry’s role will be limited to overseeing PPP projects and monitoring the outcomes, while private players will drive the implementation. There are plans for a series of PPP projects ranging from primary healthcare facilities and medical cities, to radiology and rehabilitation centres.

Similarly, Dubai Health Authority (DHA) is planning a healthcare PPP programme to establish radiology, cardiology and physiotherapy facilities across the city. In November 2018, DHA initiated the tendering process for a 110-bed Cardiac Centre of Excellence. The selected private sector entity will be responsible for designing, building, financing and operating the facility for a 25-year term.

Kuwait has also devised a model to increase the flow of PPP healthcare projects and has established the Health Assurance Hospitals Company (Dhaman), a structured PPP entity held by Kuwait Investment Authority, the Public Institution for Social Security, Arabi Group and Kuwait’s nationals. The entity currently owns and operates three facilities in the country.

There is undoubtedly an air of optimism surrounding healthcare PPPs in the GCC, but proper structure is vital to make the proposition an attractive one for all stakeholders. A balanced PPP framework will ensure a better quality of services for patients, reduced public sector expense and sustainable returns on investments for private partners, making the partnership mutually beneficial.

About the authors

Shashank Rath (far left) is a partner with Synergy Consulting IFA and leads the social infrastructure sector-related advisory. Nitesh Singh (right) is an associate at the firm

Shashank Rath (far left) is a partner with Synergy Consulting IFA and leads the social infrastructure sector-related advisory. Nitesh Singh (right) is an associate at the firm

More on this month’s cover story

- Comment: A digital prescription for Middle East healthcare

- Cover story: Digital disruption reshapes region’s healthcare sector

- Dubai Expo 2020: Raising the healthcare flag at Expo 2020

- Infographic: Middle East patients demand medicine on the move

- Vital statistics: Healthcare in numbers infographic

| This article has been unlocked to allow non-subscribers to sample MEED’s content. MEED provides exclusive news, data and analysis on the Middle East every day. For access to MEED’s Middle East business intelligence, subscribe here |

You might also like...

Energy resilience matters as much as capacity

13 March 2026

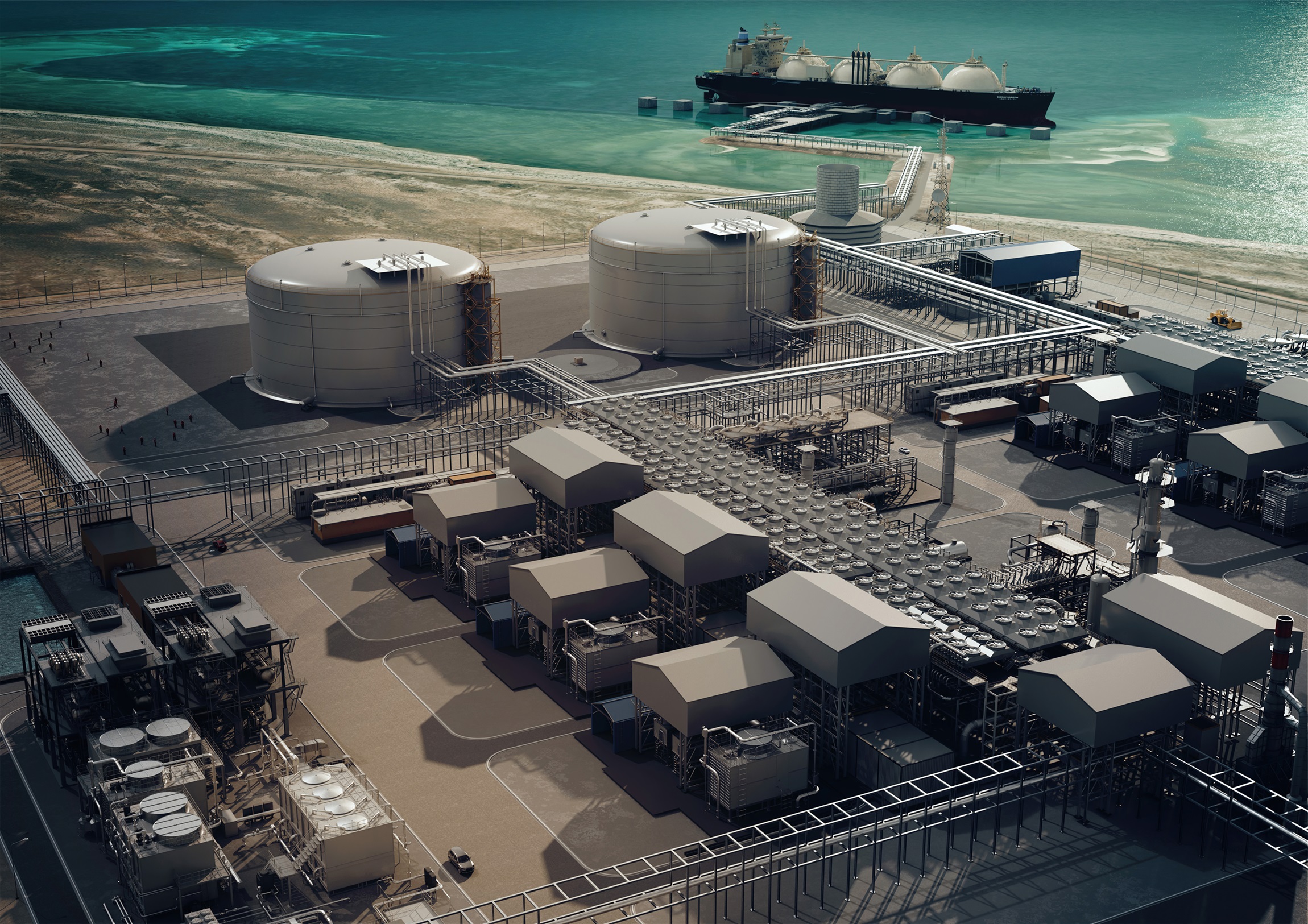

Qatar’s new $8bn investment spices up global LNG race

13 March 2026

Risk calculus shifts for regional PPP projects

13 March 2026

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.

Take advantage of our introductory offers below for new subscribers and purchase your access today! If you are an existing client, please reach out to your account manager.