Capital spending programmes are likely to be radically curtailed over the coming year, particularly when it comes to new projects

When Saudi Oil Minister Ali al-Naimi said in late October that the government was looking at the idea of cutting fuel subsidies, it merely confirmed something many outside Saudi Arabias leadership had been saying for most of the year. At a time of low oil prices, there are some difficult decisions to be made by the authorities in Riyadh. While a year ago, the idea of cutting fuel subsidies would have been all but unthinkable, now the government is having to adapt to rather different circumstances.

UK bank HSBC estimates that Saudi Arabias hydrocarbon receipts will be 45 per cent lower for 2015-17 than they were for the preceding three-year period, which it describes as the biggest terms of trade shock in a generation. It estimates that the government is facing a deficit of 19 per cent of GDP this year, and further shortfalls of 15 per cent and 11 per cent in the next two years.

Such predictions serve to highlight an uncomfortable truth for the Saudi government. Despite years of insisting that economic diversification was at the heart of its economic strategy, and despite countless billions invested in education, infrastructure and industrial developments, the government and the country as a whole are still as dependent on oil and gas revenues as ever.

Oil reliance

Diversification in Saudi Arabia has been a bit of a mirage. Any diversification that has taken place has been towards areas like petrochemicals and plastics, and they are sectors that are heavily reliant on oil, says Jason Tuvey, Middle East economist at London-based research firm Capital Economics.

So the question now is how the government can and should react to a period of fiscal constraints as a result of low oil prices. UK/US credit ratings agency Fitch Ratings estimates that the breakeven oil price for the kingdom in 2014 was about $101 a barrel. That is not going to decrease without large cuts to state spending programmes or increases in non-oil revenues, or perhaps a combination of both.

Projects planned or under way, by status

International observers have been urging the government to face up to these challenges with a comprehensive approach for some time. Tim Callen, head of the Washington-based IMFs mission to Saudi Arabia, said in September that substantial and sustained fiscal adjustment will be needed over the next few years.

Civil service

Among the measures that the government could take, Callen identified expanding non-oil revenues, reforming energy prices and controlling the public sector wage bill. Now is a good time to undertake a review of the whole civil service in Saudi Arabia, he said. To look at those positions that are really needed for [the] provision of public services and the governments economic and social programmes. Then to try and identify those positions that may not be so essential, and then over time reduce those positions as people retire from the civil service.

[Riyadh] will continue with ongoing projects but it is taking a far more conservative approach to starting new projects

Paul Gamble, Fitch Ratings

Such remedies would not be easy for the Saudi authorities to accept and the reality is that, for the sake of political expediency, the axe will fall far more heavily on capital spending programmes than on current spending. The authorities are extremely wary of prompting any discontent or protests by cutting public sector wages or pensions, for example. It is far simpler to cancel the building of a football stadium, or delay the start of construction of a motorway.

Upcoming budget

Just how quickly the government will be willing to cut large project spending remains open to question, but a partial answer may come in December when Riyadh issues its budget for the coming year. Such documents have often borne a rather tenuous connection to reality in the past; they have tended to use an overly conservative projection for oil prices, and therefore underestimate government revenues. On the other side of the accounts, they have tended to widely undershoot when it comes to state spending.

Nonetheless, the budget can offer a useful signpost of government priorities and intentions. This time, it may even be based on a more realistic forecast for oil revenues.

The expectation in the market is that capital spending programmes will be radically curtailed over the coming year, particularly when it comes to any new projects. The government will continue with ongoing projects but it is taking a far more conservative approach to starting new projects, says Paul Gamble, a director in the sovereign group at Fitch Ratings.

| Top 20 project owners* | |

|---|---|

| ($m) | |

| KA-Care | 100,000 |

| Saudi Electricity Company | 82,546 |

| Ministry of Housing | 69,741 |

| Saudi Aramco | 69,640 |

| Emaar, the Economic City | 68,430 |

| General Authority of Civil Aviation | 37,089 |

| Jeddah Development & Urban Regeneration | 37,020 |

| Saudi Railways Organisation | 34,356 |

| Saudi Basic Industries Corporation | 32,377 |

| Jeddah Economic Company | 30,000 |

| Jeddah Metro Company | 29,600 |

| Ministry of Interior | 26,271 |

| Arriyadh Development Authority | 25,260 |

| Ministry of Transport | 19,631 |

| Al-Shamiyah Urban Development | 16,250 |

| Mecca Mass Rail Transit Company | 16,000 |

| Saline Water Conversion Corporation | 13,882 |

| Khozam Development Company | 13,331 |

| Ministry of Health | 11,811 |

| Ministry of Finance | 11,685 |

| *=By value of projects planned and under way; KA-Care=King Abdullah City for Atomic & Renewable Energy. Source: MEED Projects | |

Schemes at risk

Just where the cuts will come remains, to some extent at least, a matter for conjecture. Local media reports have pointed to the cancellation of sports stadiums around the country. Road-building programmes and other elements of the countrys transport infrastructure, such as some long-distance rail lines, have also been identified as being at risk. The grand project to build a network of economic cities around the country is looking rather threadbare these days. The only one that is making significant progress is King Abdullah Economic City.

Utilities projects could also suffer. In mid-October, MEED reported that the state-owned Saudi Electricity Company had shelved a project to convert the PP9 power plant to a combined-cycle facility. The scheme would have increased the plants capacity by about 240MW. Other power and water projects could well follow in its wake.

All this is not an entirely new situation for the state. The Saudis have been in this position before, said Callen. If you go back to the drop in oil prices in the first half of the 1980s, deficits of more than 20 per cent of GDP were recorded in a couple of years.

The response then was an indication of what might happen now. Tuvey points out that during the 1980s the government cut capital spending by more than 98 per cent from peak to trough in response to low oil prices. It took until 2009 for spending to fully recover.

Recession threat

The danger is that if the cuts are too rapid and too deep, it could send the economy into recession, or at least cancel out any hopes of growth. The structure of the Saudi economy is such that any drop in government spending is likely to hit the non-oil economy quite hard. Non-oil growth is heavily dependent on government spending, particularly capital spending, says Gamble.

The most recent data from the purchasing manager index compiled by research firm Markit shows that the non-oil economy is still growing, but there are already some worrying signs. In particular, the data for new orders in September, which is a leading indicator for future economic activity, appears to be slowing down. Output also showed slower growth.

The sense of a slowing economy is reinforced by recent figures from the Gulf Projects Index, compiled by MEED. As of late October, it showed a decline in the Saudi projects market of almost 1 per cent year-on-year. While that is not a big figure, the decline is only likely to accelerate in the year ahead as government spending is pared back further.

The problem for the Saudi authorities is that the cuts to capital spending are not likely to be enough on their own to deal with the fiscal challenges the state faces. That explains the public acknowledgment by Al-Naimi that subsidies may also have to be cut.

There are some other options the government is already implementing, including using some of the savings it has squirrelled away during the years of high oil prices. The countrys central bank, the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (Sama), had some SR724bn ($193bn) in net foreign assets at the end of last year. This is according to local bank Samba, which expects that figure to have dropped to SR594bn by the end of this year and to SR520bn by the end of 2016.

Bond market

The government has also been enthusiastically tapping the bond market since the summer. Samba expects Riyadh to sell about SR100bn of bonds to local banks this year and a further SR190bn in 2016. The debt issuance is expected to cover about half the budget deficits this year and next, with the rest being paid for by the drawdown of savings.

There is, however, a further complicating factor in all this, in the shape of a relatively turbulent political environment. For Saudi Arabia, many of the recent regional developments appear threatening, including the chance of Iran re-entering the international mainstream following the deal to remove some sanctions in return for Tehran abandoning its apparent nuclear ambitions. That feeds into sectarian fears in Riyadh of a Shia crescent coming to dominate the region, from Tehran through Baghdad and Damascus.

Projects planned or under way by sector

To the south, the war in Yemen is proving both costly and increasingly intractable, and is exposing the country to allegations of war crimes against Yemens civilian population. The conflict is also throwing up some delicate domestic political issues. The campaign is closely associated with the Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the son of the king, and if it goes badly he may well suffer in any political fallout.

Unease within the royal family about the direction in which the newly installed leadership is taking the country broke into the open in September and October, when two anonymous letters, apparently written by a senior royal, leaked into the media. The letters criticised King Salman and his appointed successors, and called for the king to be replaced. How serious the threat is to the king is unclear, but the Al-Saud family has shown a willingness to act ruthlessly in the past. In the early 1960s, Prince Faisal forced King Saud from power, and was in turn assassinated in the following decade by another member of the royal family.

Political unrest

At the same time, the country faces the threat of political violence by supporters of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, and, more broadly, sectarian violence against its Shia minority in the oil-rich Eastern Province.

We expect growth to slow this year compared with 2014, but we expect it to remain robust at 2.8 per cent

Tim Callen, IMF

This complex political environment makes the decisions the government needs to take on economic issues all the more difficult. Leaders will be alert to the risk of unrest and, unlike at other times in the past, it will be more difficult for them to simply dip into their coffers and offer financial inducements to the population to remain quiet.

Having said all that, there are some positive elements. The governments low debts and large savings mean it has time to adjust its spending patterns gradually. And at this stage, most forecasters are still expecting the economy to carry on growing. Added to that, the banking system is in robust shape and can continue to lend to businesses. There is no doubt that a cut in government spending will have a detrimental effect on the economy, but it is not expected to lead to a sharp contraction as yet.

Growth in Saudi Arabia remains favourable. We do expect growth to slow this year compared with 2014, but we expect it to remain robust at 2.8 per cent, said Callen, at the time of the publication of the IMFs latest review of the Saudi economy in September. The Saudi economy is continuing to do quite well despite the oil price drop.

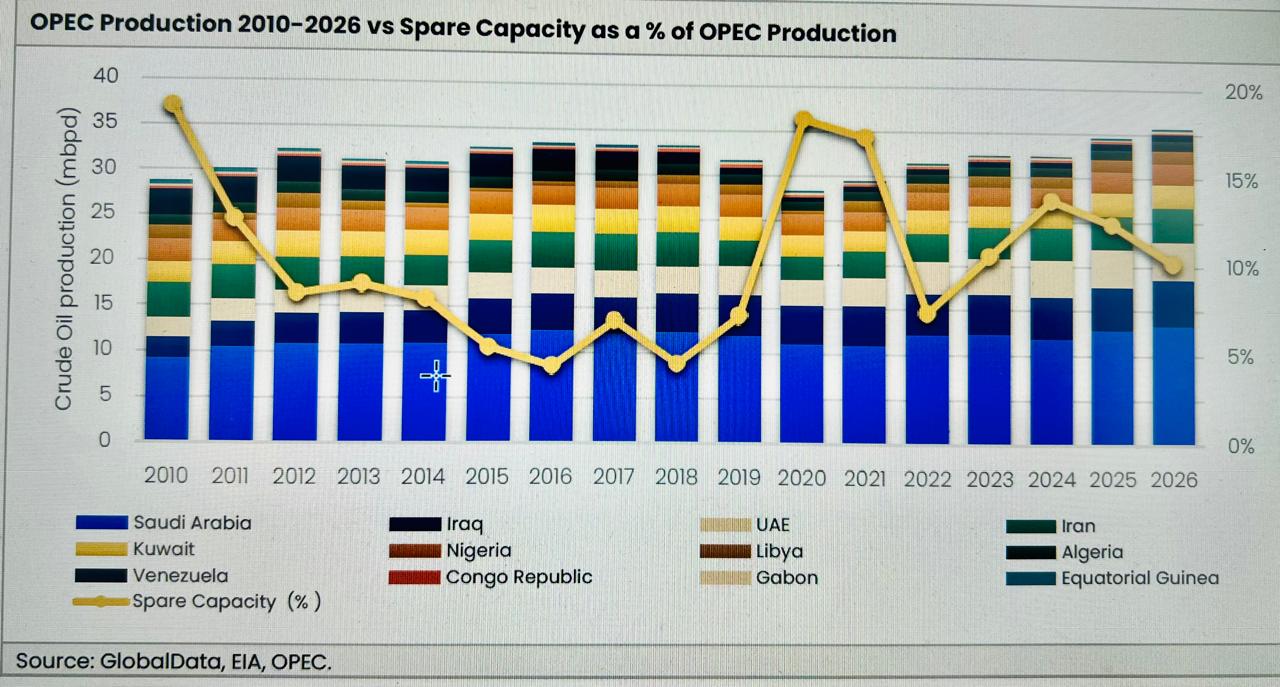

Oil prices

Ultimately, the future direction of the economy and the projects market depends largely on the direction that oil prices take in the coming months and years. Many observers suggest prices may rise gradually from late 2016 onwards. That would certainly ease the pressure on the government, but it seems unlikely that the oil price will rise by enough to cut the governments fiscal deficit entirely.

That in turn means the outlook for the projects market is likely to remain more subdued for the foreseeable future, notwithstanding the need for the country to diversify its economy and its sources of income.

Although the financial position looks OK, its the structure of the economy that is the longstanding issue, says one economist at a Saudi bank. How do they diversify and get more Saudis into the private sector, particularly with a workforce thats growing fast and a very young population? Im not seeing convincing evidence of a systematic approach to this.

I think theyre going to wait and see where the oil price goes. Its a bit of a hand-to-mouth exercise. Id hesitate to say theyre thinking in medium terms. I think they will wait to see where the price goes and if it stays flat in 2016, then theyll probably keep cutting and cut more severely. So its going to be oil price dependent.

You might also like...

Fujairah oil facility catches fire from drone debris

03 March 2026

QatarEnergy stops downstream production operations

03 March 2026

Read the March 2026 MEED Business Review

03 March 2026

Firms prepare Port of Duqm consultancy bids

03 March 2026

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.

Take advantage of our introductory offers below for new subscribers and purchase your access today! If you are an existing client, please reach out to your account manager.